The other day someone asked the question, "Does anyone use the word abide anymore?" Most of us agreed that the word had fallen into disuse and that many probably did not know its meaning. Yet it is a wonderful word, and I'm not sure there is an adequate substitute.

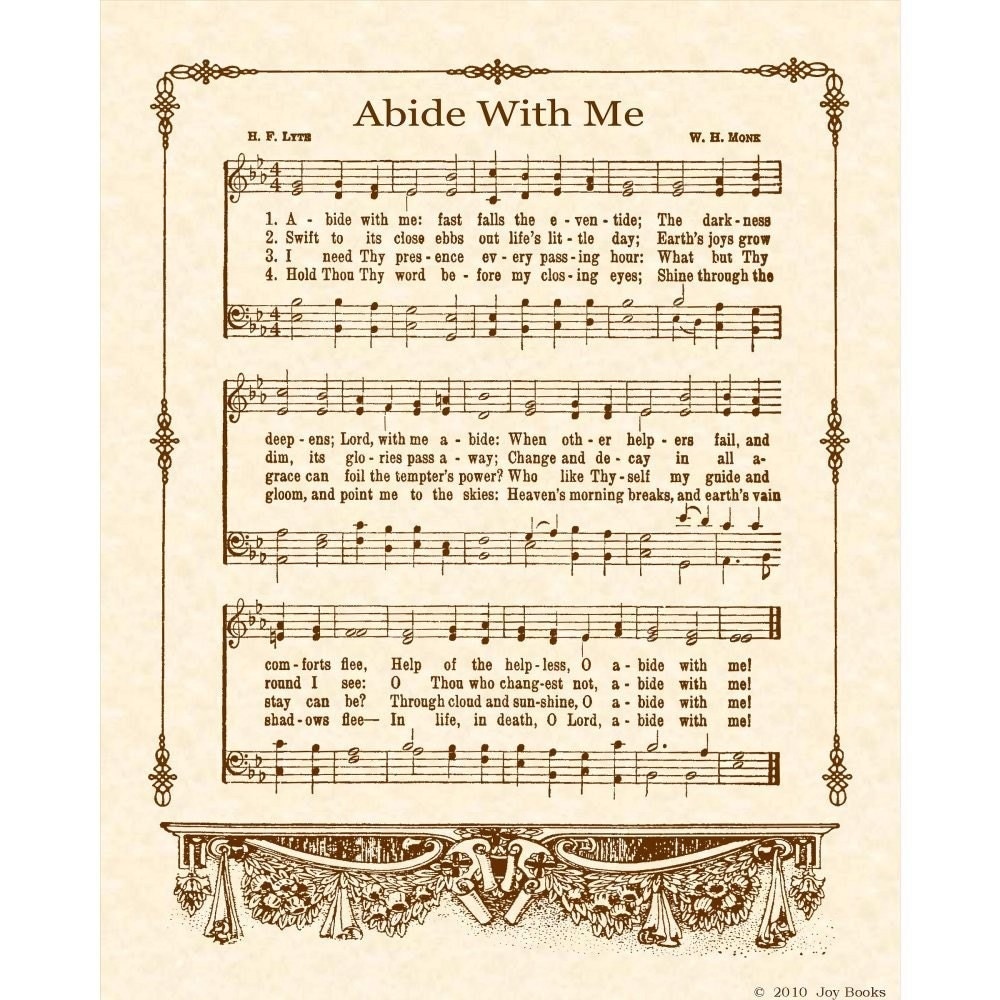

I've always loved the hymn, "Abide with Me." Being and "evening hymn," it doesn't get sung much in worship so I'm not sure how I came to appreciate it. I enjoy the tune, but I especially like all the abiding that goes on in the verses. I suppose it could be rewritten, "Remain with me," but somehow that wouldn't seem the same.

Today's gospel reading is overflowing with "abide" on the lips of Jesus. The popular NIV translation uses "remain," so I've very grateful that my NRSV sticks with "abide." Perhaps it is just me, but there seems something a bit more complex and mysterious about "abide" than "remain."

I think we in the church could use some more complex and mysterious abiding. I know I could. "Abide in me as I abide in you.

Just as the branch cannot bear fruit by itself unless it

abides in the vine, neither can you unless you abide in

me. I am the vine, you

are the branches. Those who abide in me and I in them

bear much fruit, because apart from me you can do

nothing." I in Christ and Christ in me, abiding in one another. I'm not sure "remain" quite covers that, but then again, I'm not always sure I quite understand what this "abide" is either.

I'm not sure I understand it, but I worry that I spend far too much time not abiding. Worse, I do so in my work as a pastor. Sometimes I think that it is very hard to do much abiding when you are straining or busy or working hard. It is even harder to do much abiding when you are worried and anxious. We live in an anxious world, and the church world is pretty anxious, too.

If you're not a church person, you may not know that most denominations and very many congregations are struggling with declining membership and giving. Compounding this, the average age of members is getting older and older. Survival concerns have become a driving force for many, and it is hard for anyone to completely ignore the numbers. But I'm not sure that institutional survival and abiding are compatible.

I wonder what people would think if one Sunday worship was given over to quiet reflection on abiding. Maybe we would read all the New Testament passages containing "abide" (it wouldn't take all that long), sing "Abide with Me" between the readings, and pray for Jesus to abide in us and help us abide in him. And we could just sit there and wait and wonder, and perhaps even experience a tiny bit of abiding.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Sermons and thoughts on faith on Scripture from my time at Old Presbyterian Meeting House and Falls Church Presbyterian Church, plus sermons and postings from "Pastor James," my blog while pastor at Boulevard Presbyterian in Columbus, OH.

Wednesday, April 30, 2014

Tuesday, April 29, 2014

The Gift of Not Knowing

Earlier today, I was thumbing through Graham Standish's book, Humble Leadership, looking for some quote that I had mis-remembered. (Not only had I remembered it incorrectly but it wasn't even in this book.) In the process, I stumbled onto something I had highlighted a number of years ago.

But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you. Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid. - John 14:26-27

So says Jesus to his disciples shortly before his arrest. It is a remarkable promise. The Spirit will teach us everything we need to know, and we will have true peace. I'm reasonably certain that this teaching is of a very different sort than is so stressed in my faith tradition. We Presbyterians have long demanded a highly educated clergy, well versed in theology, Bible, and so on. But this often sees being a pastor or church leader mostly as a matter of training and education, something that is almost entirely a human endeavor. Indeed at times, there is no room at all for us to be taught by the Spirit.

Our culture values accomplishment, expertise, skill, and production. But Christian faith and life in the Spirit are more about surrender and trust than they are about our abilities. Not that abilities and training don't matter, but I'm not sure they are of all that much good without the realization that, finally, God's work is beyond all our skills, demanding faith and discernment more than any expertise on our part.

This can be terribly deflating to me. I so want to be the "resident theologian," the one with clarity born of my understanding of theology and scripture. And yet the more I claim such a role for myself, the more likely I am to reinforce the culture of expertise and skill that makes it so difficult to trust in God rather than our own abilities. Not to mention how frustrated I can become if others don't trust my expertise.

At the same time, it is interesting to think that reaching a point where I don't know what to do, where I cannot find clarity, may be the very point I must come to if I am to live the abundant, Spirit-filled life Jesus wishes for me, and for all of us.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

...as we join God in an ever-deepening relationship, two things consistently happen. First, joining God in God's work leads us to a crisis of belief that requires faith and action. Most of us are under the assumption that the more we act in faith, the easier things should get. ...the opposite generally happens. Things don't get easier. Instead we end up coming to a point where we aren't sure what to do. There's little clarity. We are faced with decisions that might lead to something positive or negative, and we have no guarantees. We have no choice but to act on faith. We have to trust in God and trust in our discernment of God's will. (p. 153)I hasten to add that "discernment" is not the same thing as our deciding something. It is a spiritual process of listening for and to God, one with which many of us in the Church have precious little experience. I know I don't.

But the Advocate, the Holy Spirit, whom the Father will send in my name, will teach you everything, and remind you of all that I have said to you. Peace I leave with you; my peace I give to you. I do not give to you as the world gives. Do not let your hearts be troubled, and do not let them be afraid. - John 14:26-27

So says Jesus to his disciples shortly before his arrest. It is a remarkable promise. The Spirit will teach us everything we need to know, and we will have true peace. I'm reasonably certain that this teaching is of a very different sort than is so stressed in my faith tradition. We Presbyterians have long demanded a highly educated clergy, well versed in theology, Bible, and so on. But this often sees being a pastor or church leader mostly as a matter of training and education, something that is almost entirely a human endeavor. Indeed at times, there is no room at all for us to be taught by the Spirit.

Our culture values accomplishment, expertise, skill, and production. But Christian faith and life in the Spirit are more about surrender and trust than they are about our abilities. Not that abilities and training don't matter, but I'm not sure they are of all that much good without the realization that, finally, God's work is beyond all our skills, demanding faith and discernment more than any expertise on our part.

This can be terribly deflating to me. I so want to be the "resident theologian," the one with clarity born of my understanding of theology and scripture. And yet the more I claim such a role for myself, the more likely I am to reinforce the culture of expertise and skill that makes it so difficult to trust in God rather than our own abilities. Not to mention how frustrated I can become if others don't trust my expertise.

At the same time, it is interesting to think that reaching a point where I don't know what to do, where I cannot find clarity, may be the very point I must come to if I am to live the abundant, Spirit-filled life Jesus wishes for me, and for all of us.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Monday, April 28, 2014

Fearing the LORD

Back in my days as a pilot, I would frequently see the same poster in the airports I visited. I'm not talking about airline terminals but the part of the airport where general aviation aircraft, from little two-seaters to big corporate jets, were located. This poster was more prevalent in smaller airports where flight instructors plied their trade, teaching would-be pilots how to fly. It featured a picture of an antiquated craft from the days of bi-planes stuck in the top of a solitary tree with this quote. "Aviation in itself is not inherently dangerous. But to an

even greater degree than the sea, it is terribly unforgiving of any

carelessness, incapacity or neglect."

The origins of the quote are a bit obscure, though it may well be from the 1930s, spoken by a British aviator, Capt. A. G. Lamplugh. But regardless of who said it, the saying remains popular because of its truth. Aviation can be terribly unkind to those who do not treat it with a great deal of respect. As was once said to me when I was a young and invincible pilot. The are bold pilots, and there are old pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots."

In the Exodus story, God saves the Israelites from Pharaoh's army by creating an escape route through the sea. But when Pharaoh, the leader of the ancient world's greatest super power, attempted to follow, the army was swallowed up in the waters. "Thus the LORD saved Israel that day from the Egyptians; and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. Israel saw the great work that the LORD did against the Egyptians. So the people feared the LORD and believed in the LORD and in his servant Moses"

Interesting how the story links fear and belief, though this is far from unique. The term "fear of the LORD" occurs repeatedly in the Old Testament and a couple of times in the New as well. Perhaps the best known occurrence is from Proverbs. "The fear of the LORD is the beginning of knowledge." (Writing the word LORD in this all caps fashion is how many Bible translations continue the Jewish practice of taking great care not to speak God's personal name unless absolutely necessary. This practice uses the Hebrew word for "Lord" rather than saying YHWH, the pronunciation of which is not certain.)

This notion of fearing God is quite unnerving to many modern Christians. Yet when the book of Acts speaks of the thriving New Testament Church it says, Living in the fear of the Lord and in the comfort of the Holy Spirit, it increased in numbers." (Acts 9:31) As with Exodus linking fear and belief, Acts links fear with the comfort of the Spirit. Perhaps we should pay more attention to this fear of the LORD.

Many have pointed out that this "fear" is not about simply being terrified of God. The Hebrew word speaks of awe and respect, but that does include an element of fear. When I look upon the raging rapids of a great river surging through a canyon, I may be moved to awe and wonder, but if I get too close to the edge, fear is there, too.

I sometimes think that our being troubled by notions of fearing God is less about that being contrary to the intimacy of God's presence in Jesus and more about our very tame and domesticated ideas of God. God is often seen as a totally benign presence who give us stuff but makes no hard demands on us. In our consumer oriented society, God become a spiritual shop keeper whose job it is to give us the spiritual goodies we want, a post-modern, consumer version of what Bonhoeffer labeled "cheap grace."

But the living God is no shop keeper. Jesus tells us as much, saying that it costs us our very lives to follow him. We must deny ourselves and take up the cross. "For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it." (Matthew 16:25)

I think that the Church in our day desperately needs to discover a God who can prompt some real awe, maybe even a bit of fear. The Living God is a wild and free power who seeks to transform us, not simply to give us what we want. Writer Annie Dillard keenly observes this problem in her famous quote from Teaching a Stone to Talk.

fools despise wisdom and instruction. - Proverbs 1:7

Lord, help me wise up.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

The origins of the quote are a bit obscure, though it may well be from the 1930s, spoken by a British aviator, Capt. A. G. Lamplugh. But regardless of who said it, the saying remains popular because of its truth. Aviation can be terribly unkind to those who do not treat it with a great deal of respect. As was once said to me when I was a young and invincible pilot. The are bold pilots, and there are old pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots."

In the Exodus story, God saves the Israelites from Pharaoh's army by creating an escape route through the sea. But when Pharaoh, the leader of the ancient world's greatest super power, attempted to follow, the army was swallowed up in the waters. "Thus the LORD saved Israel that day from the Egyptians; and Israel saw the Egyptians dead on the seashore. Israel saw the great work that the LORD did against the Egyptians. So the people feared the LORD and believed in the LORD and in his servant Moses"

Interesting how the story links fear and belief, though this is far from unique. The term "fear of the LORD" occurs repeatedly in the Old Testament and a couple of times in the New as well. Perhaps the best known occurrence is from Proverbs. "The fear of the LORD is the beginning of knowledge." (Writing the word LORD in this all caps fashion is how many Bible translations continue the Jewish practice of taking great care not to speak God's personal name unless absolutely necessary. This practice uses the Hebrew word for "Lord" rather than saying YHWH, the pronunciation of which is not certain.)

This notion of fearing God is quite unnerving to many modern Christians. Yet when the book of Acts speaks of the thriving New Testament Church it says, Living in the fear of the Lord and in the comfort of the Holy Spirit, it increased in numbers." (Acts 9:31) As with Exodus linking fear and belief, Acts links fear with the comfort of the Spirit. Perhaps we should pay more attention to this fear of the LORD.

Many have pointed out that this "fear" is not about simply being terrified of God. The Hebrew word speaks of awe and respect, but that does include an element of fear. When I look upon the raging rapids of a great river surging through a canyon, I may be moved to awe and wonder, but if I get too close to the edge, fear is there, too.

I sometimes think that our being troubled by notions of fearing God is less about that being contrary to the intimacy of God's presence in Jesus and more about our very tame and domesticated ideas of God. God is often seen as a totally benign presence who give us stuff but makes no hard demands on us. In our consumer oriented society, God become a spiritual shop keeper whose job it is to give us the spiritual goodies we want, a post-modern, consumer version of what Bonhoeffer labeled "cheap grace."

But the living God is no shop keeper. Jesus tells us as much, saying that it costs us our very lives to follow him. We must deny ourselves and take up the cross. "For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it." (Matthew 16:25)

I think that the Church in our day desperately needs to discover a God who can prompt some real awe, maybe even a bit of fear. The Living God is a wild and free power who seeks to transform us, not simply to give us what we want. Writer Annie Dillard keenly observes this problem in her famous quote from Teaching a Stone to Talk.

On the whole, I do not find Christians, outside the catacombs, sufficiently sensible of the conditions. Does any-one have the foggiest idea what sort of power we so blithely invoke? Or, as I suspect, does no one believe a word of it? The churches are children playing on the floor with their chemistry sets, mixing up a batch of TNT to kill a Sunday morning. It is madness to wear ladies' straw hats and velvet hats to church; we should all be wearing crash helmets. Ushers should issue life preservers and signal flares; they should lash us to our pews. For the sleeping god may wake some day and take offense, or the waking god may draw us out to where we can never return.The fear of the LORD is the beginning of knowledge;

fools despise wisdom and instruction. - Proverbs 1:7

Lord, help me wise up.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Wednesday, April 23, 2014

Winners and Losers

God's delight is not in the strength of the horse,

nor his pleasure in the speed of a runner;

but the Lord takes pleasure in those who fear him,

in those who hope in his steadfast love. - Psalm 147:10-11

God may not delight in the strength of the horse or the speed of the runner, but most of us do. We are impressed with winners, and we don't have a lot of patience with losers. I went to Washington Nationals baseball game the other day. It was a close, low scoring affair until a relief pitcher "blew the game," giving up 4 runs in quick succession. This relief pitcher had been loudly cheered when he entered the game, but he left it to similar level of boos. He had lost. He had failed. Booooo!!

This is nothing new, of course, but I think it has taken on additional intensity in recent decades. Our world seems more and more competitive, more and more anxious, more and more stressed out. In such a setting, people are terrified of failing, and we worship those with superhuman focus and concentration, who flourish in the face of pressure, who "come through in the clutch."

In our hyper-competitive world, appearing weak is a cardinal sin. It's no wonder church folks prefer Palm Sunday and Easter to Good Friday. A cross is a place for losers, and we've never gotten completely comfortable with it. Some even go so far as to see it in "no pain - no gain" terms, as an extreme act of athletic accomplishment on the way to a remarkable victory. But that's not the picture in the gospels (at least not the synoptic ones). And it's not the picture Paul has in mind when he says Christ crucified is "a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles..." (Jew and Gentile covers all humans for Paul, and Jesus on the cross doesn't make sense from either point of view.)

Jesus says that his followers must take up their own crosses. In other words, they must embrace what the world sees as failure, becoming entirely dependent on God's care and grace. Yet even in the church, we tend to love winners and hate losers. "Successful" pastors and congregations often embody all the best leadership and business practices of our secular world, the things that will make us winners. At times we are so afraid of being losers that we become incredibly risk-averse, attempting nothing that could end in failure. We know better than to go to Jerusalem, raise a ruckus at the Temple, and challenge the authorities. What was Jesus thinking?

In my denomination, successful pastors - winners - get paid a lot more and have bigger pensions than those who are less successful - losers. In this we are little different from any other denomination. Not that I take much comfort from that. Part of our calling is to be like Jesus, to be different from the world that loves winners and hates losers. After all, Jesus spend a great deal more time with the losers than the winners. The losers tended to love him, the winner much less so.

When I think of the trouble I get myself into as a pastor, a husband, a father, a person, the lion's share of it comes from wanting so badly to be a winner and fearing so much being a loser. I don't want to admit failings of failures. I don't want to appear weak. I want to impress. I want to win. I want to be the reason things turned out well. And I think that the fear of losing is even more powerful and motivating than my desire to win.

I wonder how different my life might be, my relationships might be, if I wasn't so terrified of losing, of looking weak, of failing.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

nor his pleasure in the speed of a runner;

but the Lord takes pleasure in those who fear him,

in those who hope in his steadfast love. - Psalm 147:10-11

God may not delight in the strength of the horse or the speed of the runner, but most of us do. We are impressed with winners, and we don't have a lot of patience with losers. I went to Washington Nationals baseball game the other day. It was a close, low scoring affair until a relief pitcher "blew the game," giving up 4 runs in quick succession. This relief pitcher had been loudly cheered when he entered the game, but he left it to similar level of boos. He had lost. He had failed. Booooo!!

This is nothing new, of course, but I think it has taken on additional intensity in recent decades. Our world seems more and more competitive, more and more anxious, more and more stressed out. In such a setting, people are terrified of failing, and we worship those with superhuman focus and concentration, who flourish in the face of pressure, who "come through in the clutch."

In our hyper-competitive world, appearing weak is a cardinal sin. It's no wonder church folks prefer Palm Sunday and Easter to Good Friday. A cross is a place for losers, and we've never gotten completely comfortable with it. Some even go so far as to see it in "no pain - no gain" terms, as an extreme act of athletic accomplishment on the way to a remarkable victory. But that's not the picture in the gospels (at least not the synoptic ones). And it's not the picture Paul has in mind when he says Christ crucified is "a stumbling block to Jews and foolishness to Gentiles..." (Jew and Gentile covers all humans for Paul, and Jesus on the cross doesn't make sense from either point of view.)

Jesus says that his followers must take up their own crosses. In other words, they must embrace what the world sees as failure, becoming entirely dependent on God's care and grace. Yet even in the church, we tend to love winners and hate losers. "Successful" pastors and congregations often embody all the best leadership and business practices of our secular world, the things that will make us winners. At times we are so afraid of being losers that we become incredibly risk-averse, attempting nothing that could end in failure. We know better than to go to Jerusalem, raise a ruckus at the Temple, and challenge the authorities. What was Jesus thinking?

In my denomination, successful pastors - winners - get paid a lot more and have bigger pensions than those who are less successful - losers. In this we are little different from any other denomination. Not that I take much comfort from that. Part of our calling is to be like Jesus, to be different from the world that loves winners and hates losers. After all, Jesus spend a great deal more time with the losers than the winners. The losers tended to love him, the winner much less so.

When I think of the trouble I get myself into as a pastor, a husband, a father, a person, the lion's share of it comes from wanting so badly to be a winner and fearing so much being a loser. I don't want to admit failings of failures. I don't want to appear weak. I want to impress. I want to win. I want to be the reason things turned out well. And I think that the fear of losing is even more powerful and motivating than my desire to win.

I wonder how different my life might be, my relationships might be, if I wasn't so terrified of losing, of looking weak, of failing.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Tuesday, April 22, 2014

Did Anything Really Happen?

O sing to the LORD a new song,

for he has done marvelous things.

His right hand and his holy arm

have gained him victory.

The LORD has made known his victory;

he has revealed his vindication in the sight of the nations. He has remembered his steadfast love and faithfulness

to the house of Israel.

All the ends of the earth have seen

the victory of our God. Psalm 98:1-3

For pastors and other church professionals, the week following the celebration of the Resurrection may feature more of a collective sigh and collapse than the days right after Christmas. Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday (and for some a vigil on Saturday) is followed by special music and fanfare for Easter Sunday itself, complete with sunrise services and other extras. Liturgically speaking, we go wild for Easter - and not without good reason - and then...?

On Easter I preached about how resurrection was so much more than butterflies and natural processes, so much more than the promise of life after death. I said it was about God intervening in human history to do something wonderfully and frighteningly new. But in the post-Easter letdown, things can seem terribly "back to normal."

Traditional Christian theology has spoken of the cross and resurrection as marking the close of an old age even though the age to come has not yet fully arrived. And so we live in "the time between the times," an interlude in history between how things have always been and how they will be in God's new day, what Jesus called the Kingdom. During this between time, we experience God's new day only provisionally, in the community of faith as it becomes the body of Christ, and within us through the presence of the Holy Spirit. But I must confess that the world/age that is passing away often seems much more real to me than that day that is coming, that Kingdom and newness that I proclaimed on Easter. And the post-Easter letdown only aggravates such feelings.

I sometimes worry about the future of the Church and my own Presbyterian denomination because it seems so institutional, so far from a Spirit filled beacon of God's new day. Over the years many have written about congregations and denominations that depend solely on their own resources, rarely doing anything that would be possible only with God's help. Such writings resonate with me, but if I am honest, I have to say that I'm as caught up in such patterns as anyone. I'll work hard and urge others to do the same, but I doubt anything significant will happen beyond our efforts.

Did anything really change because of the resurrection? It apparently did for those first disciples. The contrast between those who so regularly failed to understand and who scattered and denied when Jesus was arrested compared with the disciples who spread the gospel all over the Mediterranean at great personal risk and even death is remarkable. And they didn't have any of the books and consultants and resources and conferences that are available to me.

Sometimes I think the greatest challenge facing pastors like myself is not the need to figure out all the management, leadership, or programmatic tricks to help churches do well. Rather it is living as though something really happened nearly 2000 years ago that changed everything.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

for he has done marvelous things.

His right hand and his holy arm

have gained him victory.

The LORD has made known his victory;

he has revealed his vindication in the sight of the nations. He has remembered his steadfast love and faithfulness

to the house of Israel.

All the ends of the earth have seen

the victory of our God. Psalm 98:1-3

For pastors and other church professionals, the week following the celebration of the Resurrection may feature more of a collective sigh and collapse than the days right after Christmas. Palm Sunday, Maundy Thursday, Good Friday (and for some a vigil on Saturday) is followed by special music and fanfare for Easter Sunday itself, complete with sunrise services and other extras. Liturgically speaking, we go wild for Easter - and not without good reason - and then...?

On Easter I preached about how resurrection was so much more than butterflies and natural processes, so much more than the promise of life after death. I said it was about God intervening in human history to do something wonderfully and frighteningly new. But in the post-Easter letdown, things can seem terribly "back to normal."

Traditional Christian theology has spoken of the cross and resurrection as marking the close of an old age even though the age to come has not yet fully arrived. And so we live in "the time between the times," an interlude in history between how things have always been and how they will be in God's new day, what Jesus called the Kingdom. During this between time, we experience God's new day only provisionally, in the community of faith as it becomes the body of Christ, and within us through the presence of the Holy Spirit. But I must confess that the world/age that is passing away often seems much more real to me than that day that is coming, that Kingdom and newness that I proclaimed on Easter. And the post-Easter letdown only aggravates such feelings.

I sometimes worry about the future of the Church and my own Presbyterian denomination because it seems so institutional, so far from a Spirit filled beacon of God's new day. Over the years many have written about congregations and denominations that depend solely on their own resources, rarely doing anything that would be possible only with God's help. Such writings resonate with me, but if I am honest, I have to say that I'm as caught up in such patterns as anyone. I'll work hard and urge others to do the same, but I doubt anything significant will happen beyond our efforts.

Did anything really change because of the resurrection? It apparently did for those first disciples. The contrast between those who so regularly failed to understand and who scattered and denied when Jesus was arrested compared with the disciples who spread the gospel all over the Mediterranean at great personal risk and even death is remarkable. And they didn't have any of the books and consultants and resources and conferences that are available to me.

Sometimes I think the greatest challenge facing pastors like myself is not the need to figure out all the management, leadership, or programmatic tricks to help churches do well. Rather it is living as though something really happened nearly 2000 years ago that changed everything.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Sunday, April 20, 2014

Sermon: All Heaven Breaks Loose

Matthew 28:1-10

All Heaven Breaks Loose

James Sledge April

20, 2014 – Resurrection of the Lord

If

you’ll pardon the expression, there’s a whole lot of shaking going on in

Matthew’s account of Holy Week and the Resurrection. It started on Palm Sunday

although it’s easy to miss that in the English translation. There it says that

when Jesus had entered Jerusalem, the whole city was in turmoil, but

the word more literally means “shaken,” a word most often associated with

earthquakes and the root of our word “seismic.”

The

same shaking occurs when Jesus dies on the cross, an earthquake that leads the

centurion and those with him to say, “Surely this man was God’s son.” And

now on Easter morning, the shaking continues. An angel comes down from heaven

to roll back the stone, setting off a great earthquake. This angel causes the

guards to shake as well and become like dead men. Like I said, there’s a whole

lot of shaking going on.

All this shaking is Matthew’s way of

saying that something of cosmic proportions is happening. Earthquakes and

angels are about the power of God bursting forth, about all heaven breaking

loose.

___________________________________________________________________________

A

lot of you may not know about it, but our denomination recently put out a new

hymnal. I love it. It has a lot more music than our current one, including lots

of different kinds of music, music from the Iona and Taizé communities and from

different world cultures. It’s a great hymnal, but when I was looking through

the hymns and songs it has for Easter, I was a bit surprised, maybe even disappointed,

to find one called “In the Bulb There Is a Flower.”

Some

of you may know it. It’s a nice, pleasant tune that is easy to sing, but I’m

less sure about its theology. “In the bulb there is a flower; in the seed, an

apple tree; in cocoons, a hidden promise: butterflies will soon be free! In the

cold and snow of winter there’s a spring that waits to be, unrevealed until its

season, something God alone can see.”

It

is true that bulbs turn to flowers, cocoons hold fledgling butterflies, and

winter gives way to spring, but none of that has much to do with resurrection,

to God’s power bursting forth and all heaven breaking loose. When two women

named Mary go to a graveyard early one Sunday morning, they do not find spring,

or butterflies, or daffodils, and if they had, it would not have been big news.

When

Mary Magdalene and another Mary go to the cemetery, they expect nothing more

than any of us do when we go to a cemetery to pay our respects. As Barbara

Brown Taylor says in one of her Easter sermons, “When a human being goes into

the ground, that is that. You do not wait around for the person to reappear so

you can pick up where you left off—not this side of the grave, anyway. You say

good-bye. You pay your respects and go on with your life the best you can,

knowing that the only place springtime happens in a cemetery is on the graves,

not in them.”[1]

But

as Matthew has already alerted us via earthquakes and angel, something cosmic

and unnatural is happening. God is doing something completely new and

unprecedented. This has nothing to do with natural processes, nor with eternal

souls that continue on after death. It is about heaven erupting on earth. When

Jesus bursts from the tomb, it’s not about creating an escape route from earth

for believers. It is the opening event in heaven’s invasion of earth, the first

act in the coming of God’s new day, that event we pray for each week saying,

“Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

When

we gather to celebrate the resurrection today and on every Sunday, on every day

of resurrection, we proclaim so much more than life after death. We proclaim

heaven breaking loose, God’s resurrection power shaking things up. It is something

so different and new and powerful that it is more than a little frightening for

those who encounter it, which is why both the angel and Jesus must say, “Do

not be afraid.” This power can

be especially frightening to religious folks because it cannot be controlled,

and we do like things controlled.

But

God’s power that shakes things up is also a power that makes all things,

including us, new. It is God’s wild and free power to make us truly alive. It

is, writes Walter Brueggemann, “…new surging possibility, new gestures to the

lame, new ways of power in an armed, fearful world, new risk, new life,

leaping, dancing, singing, praising the power beyond all our controlled powers.”

[2]

It

is the cosmic power of heaven, of God, breaking into our lives and into our

world, and that is even more wonderful than it is frightening.

Christ

is risen! Alleluia! Thanks be to God.

Friday, April 18, 2014

God's Absence

I just returned from our local, ecumenical Good Friday service. We followed the same format as last year (my first at the service) where pastors from various congregations reflected on the "seven last words of Christ." We each were assigned a verse relating something Jesus said from the cross. My verse was the one where Jesus quotes today's morning psalm, Psalm 22. "My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?"

I can only imagine that what Jesus experienced was a terrifically amped-up version of something many of us have felt, the absence of God. I've certainly experienced it, as have many I've talked to: those moments when life seems to be falling apart, when everything has gone wrong, when the world seems hopeless and hell-bent on self destruction, and God is nowhere to be found. When it happens to me with enough force, it can make me doubt my previous experience of God and make me wonder about the faith I profess. But how about Jesus?

Jesus' sense of God's presence, his intimacy with God, surely made the experience of God's absence even more terrifying. Given who he was, could he doubt God's very existence? And if he could not, what conclusion did that leave. Had God abandoned him? Was he now alone and on his own? As I said, I can only imagine what might have gone through Jesus' mind, and I don't care to experience such depth of suffering myself.

Who wants to suffer or wishes suffering on themselves? Certainly much suffering is pointless and destructive, but by no means all of it. I've been touched of late by David Brooks' NY Times column "What Suffering Does," as well as Barbara Brown Taylor's recent work on darkness. Add to that books such as Richard Rohr's Falling Upward and the writings of other spiritual giants who do not wish suffering on anyone but who also know its potential to be grace filled. As Julian of Norwich once wrote, Firsts there is the fall, and then we recover from the fall. Both are the mercy of God!"

As David Brooks says, we live in a culture obsessed with happiness, yet we know, deep in our bones, about the power of suffering to shape and mold us, to help us "fall upward." I don't know if any of this applies to Jesus on the cross, but I find such a notion much more palatable than some of the brutal, substitutionary atonement posts by some of my Facebook friends. If Jesus had to suffer and die - and it seems he did - I hope it was not because God had to kill someone. Even if Jesus did jump up and take the bullet for us, we're still left with a terrible sort of God who must have blood.

And so I find myself looking upon Jesus, reflecting on the abandonment he felt, the suffering he endured, and wondering about if or how it changed him, wondering about its necessity and if that is so far removed from the fact that all human life entails suffering.

_______________________________________________________________________

We'll have our own Good Friday Tenebrae service at this church tonight. We'll hear once more the story of betrayal, arrest, trial, and execution. We'll sing mournful songs and sit in silence, reflecting on the deepening darkness. ...And we'll hope, as does the psalm Jesus quotes from the cross, that all this leads somewhere good.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

I can only imagine that what Jesus experienced was a terrifically amped-up version of something many of us have felt, the absence of God. I've certainly experienced it, as have many I've talked to: those moments when life seems to be falling apart, when everything has gone wrong, when the world seems hopeless and hell-bent on self destruction, and God is nowhere to be found. When it happens to me with enough force, it can make me doubt my previous experience of God and make me wonder about the faith I profess. But how about Jesus?

Jesus' sense of God's presence, his intimacy with God, surely made the experience of God's absence even more terrifying. Given who he was, could he doubt God's very existence? And if he could not, what conclusion did that leave. Had God abandoned him? Was he now alone and on his own? As I said, I can only imagine what might have gone through Jesus' mind, and I don't care to experience such depth of suffering myself.

Who wants to suffer or wishes suffering on themselves? Certainly much suffering is pointless and destructive, but by no means all of it. I've been touched of late by David Brooks' NY Times column "What Suffering Does," as well as Barbara Brown Taylor's recent work on darkness. Add to that books such as Richard Rohr's Falling Upward and the writings of other spiritual giants who do not wish suffering on anyone but who also know its potential to be grace filled. As Julian of Norwich once wrote, Firsts there is the fall, and then we recover from the fall. Both are the mercy of God!"

As David Brooks says, we live in a culture obsessed with happiness, yet we know, deep in our bones, about the power of suffering to shape and mold us, to help us "fall upward." I don't know if any of this applies to Jesus on the cross, but I find such a notion much more palatable than some of the brutal, substitutionary atonement posts by some of my Facebook friends. If Jesus had to suffer and die - and it seems he did - I hope it was not because God had to kill someone. Even if Jesus did jump up and take the bullet for us, we're still left with a terrible sort of God who must have blood.

And so I find myself looking upon Jesus, reflecting on the abandonment he felt, the suffering he endured, and wondering about if or how it changed him, wondering about its necessity and if that is so far removed from the fact that all human life entails suffering.

_______________________________________________________________________

We'll have our own Good Friday Tenebrae service at this church tonight. We'll hear once more the story of betrayal, arrest, trial, and execution. We'll sing mournful songs and sit in silence, reflecting on the deepening darkness. ...And we'll hope, as does the psalm Jesus quotes from the cross, that all this leads somewhere good.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Thursday, April 17, 2014

Part of Salvation History

Christian Seders or not, all the gospel accounts want to connect the events of Holy Week to the Passover. But I do not think they do so in any attempt to take over or supersede Jewish faith or practice (something the aforementioned blog post worries about happening with Christian Seders). Rather they want to connect the events of Jesus' death and resurrection to God's saving acts, and number one on that list is God rescuing slaves from Egypt in the Exodus.

To my mind, a grave mistake made by many Christian traditions is spiritualizing "salvation," transforming it from concrete, historical acts of rescue into a ticket to heaven when you die. The salvation of Exodus rescues the Hebrews in order to form them into the people of Israel, a peculiar community ordered very differently from the kingdoms of the world. And Jesus' own teachings about the kingdom of God are very much in keeping with this, about God's continuing work within history to create a community that reflects the ways of God rather than those of "the world."

One of the reasons I am okay with "Christian Seders" (done with care and sensitivity) is that we need to locate Christian notions of salvation within the larger scope of salvation history. Doing that is not about taking over or superseding Jewish practice. It is about letting such practice reeducate us on just what salvation is about. (I got this notion of being "reeducated by Judaism" from Walter Brueggemann in his book Sabbath as Resistance, where he says, "As in so many things concerning Christian faith and practice, we have to be reeducated by Judaism that has been able to sustain its commitment to Sabbath as a positive practice of faith." And I think salvation is one of those "so many things.")

____________________________________________________________________________

Presbyterians don't use the language of "personal salvation" as much as some other Christian groups, but the idea has profound impact on us nonetheless. Many of us think of salvation as a personal, individual thing, even if we never speak of "being saved." But neither the Exodus nor the kingdom of God can happen to individuals. Such events in salvation history are profoundly corporate. God rescues people, not individual souls, and it would do Christians a world of good if our understanding of salvation was, in large part, defined by Passover and the events of the Exodus.

I take it that the gospel writers share such notions. That may explain why "Passover" is spoken four times - with "Unleavened Bread" thrown in for good measure - in the opening of today's reading from Mark. Jesus' salvation must be a lot like that one.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Wednesday, April 16, 2014

Serving the Owner

Today's lectionary readings contain Jesus' last parable in the gospel of Mark. The parable itself is told to opponents of Jesus, in this case chief priests, scribes, and elders, on the day after Jesus has "cleansed the Temple." Following an exchange with them about the nature of his authority, Jesus tells of a man who planted a fine vineyard and added all that was needed for producing wine. He then leased it to tenants. This lease involved the owner receiving a percentage of the wine the tenants produced. This would have been typical practice in the ancient Middle East, but in the parable, the tenants refuse to pay up. They beat or killed servants sent to collect the rent. They even killed the owner's son.

The meaning of the parable is painfully obvious to Jesus' opponents, maybe more so than it would have been to us. After all, the Temple functioned very much like the vineyard in the parable . Priests kept a share of the offerings of money and animals for their own use. Nothing wrong with that. Most church congregations function is a similar manner. Pastors and other employees get a portion of people's offerings. And the offerings also provide members with things they like, which may or may not have anything to do with serving God.

Jesus clearly thinks this sharing of the offerings has gotten out of whack at the Temple. No doubt there were faithful people who came to it and had profound religious experiences, who brought sacrifices and offerings from deep, religious motives. But on balance, Jesus seems to think that things have become hopelessly corrupted, about something other that God and God's will.

I wonder what sort of parable Jesus would tell to the congregations you and I frequent. The parable in today's gospel seems to expect that we will get something out of our work in such congregations, but it also expects that God will get something as well. To push the metaphor a bit, the Church belongs to God, and while we receive something for our service, we worship and work in it for the sake of the owner. Or at least we are supposed to.

Where is the boundary line that separates good tenants from wicked ones? At what point does church become so much about us and what we want that we have stopped serving the owner? It's probably less a bright, clear line than it is an ill-defined transition zone, but at some point a congregation moves out of that zone into the "Well done, good and faithful servant" side or to the wicked tenant side.

I have a sneaky suspicion that figuring this out is largely about who a congregation exists for. What part of what we do is purely for us, and what part is for others, for those Jesus sought out and ministered to? And I am all too aware of how tempting it is to do church for me and others like me. This takes many forms. It is worship designed to please me and my friends and children, programs meant for me and my friends and children, activities for me and my friends and children, etc. And church budgets often provide hard numbers on how much a congregation serves me and mine and how much it serves the owner.

______________________________________________________________________________

One of the lessons young children must learn in order to grow up and become reasonably well adjusted adults is discovering that they are not the center of the universe. Children who do not learn such lessons are often quite miserable themselves, and they almost always make everyone around them miserable.

When it comes to faith and life with God, I often feel like a child who is still learning what it means to be a mature member of God's household. I'm stubborn and hard-headed, and I've still not quite gotten that I'm not the center and it's not all about me. But deep down I know that in reality, first and foremost, it's about serving the owner, and serving the other.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

The meaning of the parable is painfully obvious to Jesus' opponents, maybe more so than it would have been to us. After all, the Temple functioned very much like the vineyard in the parable . Priests kept a share of the offerings of money and animals for their own use. Nothing wrong with that. Most church congregations function is a similar manner. Pastors and other employees get a portion of people's offerings. And the offerings also provide members with things they like, which may or may not have anything to do with serving God.

Jesus clearly thinks this sharing of the offerings has gotten out of whack at the Temple. No doubt there were faithful people who came to it and had profound religious experiences, who brought sacrifices and offerings from deep, religious motives. But on balance, Jesus seems to think that things have become hopelessly corrupted, about something other that God and God's will.

I wonder what sort of parable Jesus would tell to the congregations you and I frequent. The parable in today's gospel seems to expect that we will get something out of our work in such congregations, but it also expects that God will get something as well. To push the metaphor a bit, the Church belongs to God, and while we receive something for our service, we worship and work in it for the sake of the owner. Or at least we are supposed to.

Where is the boundary line that separates good tenants from wicked ones? At what point does church become so much about us and what we want that we have stopped serving the owner? It's probably less a bright, clear line than it is an ill-defined transition zone, but at some point a congregation moves out of that zone into the "Well done, good and faithful servant" side or to the wicked tenant side.

I have a sneaky suspicion that figuring this out is largely about who a congregation exists for. What part of what we do is purely for us, and what part is for others, for those Jesus sought out and ministered to? And I am all too aware of how tempting it is to do church for me and others like me. This takes many forms. It is worship designed to please me and my friends and children, programs meant for me and my friends and children, activities for me and my friends and children, etc. And church budgets often provide hard numbers on how much a congregation serves me and mine and how much it serves the owner.

______________________________________________________________________________

One of the lessons young children must learn in order to grow up and become reasonably well adjusted adults is discovering that they are not the center of the universe. Children who do not learn such lessons are often quite miserable themselves, and they almost always make everyone around them miserable.

When it comes to faith and life with God, I often feel like a child who is still learning what it means to be a mature member of God's household. I'm stubborn and hard-headed, and I've still not quite gotten that I'm not the center and it's not all about me. But deep down I know that in reality, first and foremost, it's about serving the owner, and serving the other.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Monday, April 14, 2014

Sunday, April 13, 2014

Sermon: A Parade from the Underside

Matthew 21:1-11

A Parade from the Underside

James Sledge April

13, 2014

Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of

the Lord! There are no

waving palms in Matthew’s account of Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem, but that’s a

minor detail. Waving our palms seems perfectly fitting when we join the parade

as the king, the Son of David, enters into the holy city.

It

is a parade, but there are all sorts of parades. We have inauguration parades

in DC when a new president takes office, sort of like a new king. But for a

modern day example of an ancient king’s coronation parade, I picture a first

century version of one of those elaborate military parades in North Korea,

where Kim Jong-un watches all the tanks and missiles and high-stepping soldier

march by. In Jesus’ day it would have been horses and chariots and Roman

legions in finest attire, but it’s the same idea.

But

Jesus’ parade looks nothing like that. There is no official entourage. There

are no soldiers, no weapons. There are no colorful banners or elaborate

decorations. Matthew tells us without question that God is involved, that

Scripture is being fulfilled. But beyond that, the whole thing feels impromptu.

The crowd, which functions in Matthew’s gospel as a single character, a kind of

13th disciple, covers the road with branches and their own clothes

as they loudly proclaim the arrival of this one long promised.

This

is parade from the underside, the sort of parade likely to cause trouble

because it frightens the powers-that-be. A new king challenges the present rulers

and the status quo. In a sense, this parade may feel a bit like an early civil

rights march in the deep south. Many of us have vivid memories of how those

marchers were greeted with fire hoses and beatings. It was even worse for those

who marched against apartheid in South Africa. And so we should know that

things will not end well for Jesus.

Jesus’

parade is a counter cultural one because he is a threat to all earthy powers.

He is a threat to the powers that many of us serve. This king is a threat to

military powers and to those who trust in such power. He is a threat to

economic powers that concentrate wealth in the hands of a few, nations or

people. He is a threat to the consumerism that rules many of our lives, telling

us, “You

cannot serve two masters… You cannot serve God and wealth,” but still

we try. Jesus is a threat to our overly competitive, 24/7 culture, commanding

us, “Do

not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, or about

your body, what you will wear,” yet we still do.

Jesus

is a threat, and so the Jerusalem powers-that-be must deal with him, as

powers-that-be must still do. In Jesus’ day, they used a cross. Today, we’ve

grown more sophisticated, enlisting even the Church to minimize the threat by

saying that Jesus’ kingdom is only a spiritual one, only about your eternal

soul, with no designs on lifting up the poor, releasing the captive, or freeing

us from our slavery to possessions, success, money, and more.

Jesus

is a threat to all earthly power, but for the moment, the crowd in Jerusalem

embraces him anyway. They recognize that this one, so different from the

conquering-hero Messiah people were expecting, is indeed the promised Son of

David.

The

crowd, like the other disciples, will abandon Jesus when he is arrested. Like

Peter, they will deny him. Neither disciples nor crowd can yet envision that this

humble Messiah’s power is greater than the powers-that-be, greater than the

cross and even death itself. They have

not yet encountered the power of resurrection.

Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of

the Lord!

We wave our palms and join the parade, this countercultural parade from the

underside that threatens all powers-that-be. We know this parade frightens those powers,

and that it leads to a cross. But we also know of the power of resurrection,

power far greater than anything the world knows.

Hosanna! Blessed is the one who comes in the name of

the Lord! As his followers, let us continue to march,

to proclaim, to agitate, and to work for God’s new day, where love will triumph

over all the powers-that-be, and God’s will shall rule, in our hearts and in

all the world.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)