I have many things to be thankful for. The list is long enough that I won't even try to catalog them here, but I will mention the special blessings I've received this year via friends at the Institute of Islamic and Turkish Studies in Fairfax, VA. Not only did my congregation have the wonderful opportunity to break the Ramadan fast with the congregation from IITS's Ezher Mosque, but I and pastors from several area congregations enjoyed a ten day trip to Turkey with their Imam, Bilal, thanks to their generosity and hospitality. In fact, the "Thanksgiving Feast" pictured here is actually one of several meals our group enjoyed in people's homes in Turkey.

While visiting Turkey, we were received with amazing graciousness and hospitality. We feasted on wonderful food. And we experienced remarkable warmth and love from people we had never before met. This was in part because of the hospitality that is a big part of Mediterranean culture, and because such hospitality is a central part of Islam, as it is with Judaism and Christianity.

As I give thanks for my friends at IITS and in Turkey, I am saddened and frightened by the tone of political discourse that speaks openly of registering Muslims. That sadness only deepened as I read an article in yesterday's Washington Post entitled, "Americans are increasingly skeptical of Muslims. But most Americans don't talk to Muslims." The article contains the startling statistics that a majority of Americans thing Islam is at odds with American values while 70 percent of Americans have seldom or never spoken to a Muslim.

People who are my friends, people who have treated me with the utmost courtesy, hospitality, and respect, are being demonized and scapegoated in large part because ridiculous stereotypes of Islam go unchallenged by actual encounters and experiences with living, breathing Muslims.

Most of us are familiar with disgusting stereotypes of Jews, African Americans, gays, etc. But most of us also know at least a few Jews, African Americans, gays, etc. and so we know real people who don't fit the stereotypes. Apparently most Americans cannot say that with regard to Muslims.

I have a troubling suspicion that this is also the case for many Americans and Jesus. Based on a lot of rhetoric that gets passed off as "Christian," I have to wonder if these people have ever met the Jesus portrayed in the pages of the Bible or if they only know some popular stereotype of Jesus they encountered who knows where.

There are ridiculous stereotypes of Jesus on both the left and the right. In the worst cases of both, there is a willful attempt to reshape Jesus to fit people's particular political views. But the bigger problem seems to be similar to that with Muslim stereotypes. People simply accept stereotypes because no actual experience with Jesus challenges them.

Especially for Protestants, this problem is largely one of failing to regularly and seriously engage with the Scriptures. Huge swaths of American Christianity seem perfectly content to assume that the Jesus of the Bible largely conforms to their stereotypes. They may even know of a few Bible passages that buttress that stereotype, but their Jesus almost never confounds or challenges them. Yet the biblical Jesus did that on a regular basis, both with the religious establishment of his day and with his own followers.

When you hear Donald Trump or some other candidate talking about Muslims, who is that to you? What comes to mind when you hear the words Muslim or Islam, and where do these images come from? And what about Jesus? What comes to mind when you hear his name, and where did that image come from?

Seems to me that with both Islam and Jesus, a lot of foolishness, a lot of hate, and a lot of harm, arise because people have so little experience with the reality of either.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Sermons and thoughts on faith on Scripture from my time at Old Presbyterian Meeting House and Falls Church Presbyterian Church, plus sermons and postings from "Pastor James," my blog while pastor at Boulevard Presbyterian in Columbus, OH.

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

Monday, November 23, 2015

Sunday, November 22, 2015

Sermon: Embracing the Truth

John 18:33-37

Embracing the Truth

James Sledge November

22, 2015 (Christ the King)

“What is truth?” That is

Pilate’s response when Jesus says, “For this I was born, and for this I came

into the world, to testify to the truth. Everyone who belongs to the truth

listens to my voice." And so Pilate cuts off Jesus’ attempt to

engage Pilate the man, the person behind the persona.

On

the surface, Pilate is the most powerful man in all of Jerusalem, in all of

Palestine. He is Roman governor, with the power and authority of the Roman

Empire and the might of the Roman army at his disposal. He has the power of

life and death over Jesus and countless others. Yet the gospel of John

describes a scene where Pilate is the one on trial, where he is a pawn caught

up in events he cannot control.

In

John’s account of Pilate’s trial before Jesus, Pilate is a tragic, even comic

figure. Amidst all his trappings of power, he must scurry back and forth

between Jesus and the Jewish authorities gathered outside, and as the events

unfold, Pilate grows more and more frightened, and more and more aware that he

is trapped. So much for all that power.

In

the portion of this trial that we hear this morning, Jesus responds to Pilate’s

questions with questions of his own, or answers that reshape the conversation.

In a manner reminiscent of his conversations with Nicodemus or a Samaritan

women at a well, Jesus invites Pilate to see things differently. Even at his

own trial, Jesus reaches out and ministers to Pilate, offering him a chance to

let go of assumptions and patterns that trap him, to grow and step into the

truth. But it is more than Pilate can do. It would be far too costly for him.

I

think most any modern politician can appreciate Pilate’s predicament. Think of

all the ways politicians and office holders find themselves boxed in, unable to

speak what they truly believe or think. Are all those increasingly absurd

statements about Syrian refugees and Muslims really heartfelt, well-reasoned

responses? Or do the people making them feel forced to speak a certain way, trapped

just like Pilate.

People

regularly trash politicians for dancing around the truth, for the way they

“spin” and massage the truth, but there is often a price for them to pay if

they don’t. Democrat or Republican, conservative or liberal, most all discover

that their notions of power and control are as much illusions as was Pilate’s.

There are things they must say and do, and things they cannot.

But

I need not pick on politicians. Fact is, most of us live behind masks and

personas. Perhaps not so blatant as Pilate’s or some politicians, but there are

plenty of times when I am frightened of the truth, when I’m not inclined to let

Jesus draw me out of my fears.

As a pastor, I am supposed to know and

embody certain things. There are certain assumptions about who I am and how I

should act. Some of those are my own assumptions that I have acquired from God

knows where, and some are assumptions that others have for me. Much like

Pilate, I can find myself caught in these assumptions and expectations without

much thought for truth.

Wednesday, November 18, 2015

Fear and Foreigers

The Old Testament book of Ezra tells of events when Jewish exiles in Babylon are permitted to return to Israel and begin rebuilding Jerusalem. Prophets had spoken of a day when exiles returned and Jerusalem became great again, surpassing the glory of David and Solomon. But it didn't work out quite that way. Jerusalem remained a shell of its former self, an insignificant, backwater town.

Naturally there were people who looked for something or someone to blame. Perhaps they weren't pure enough to please God, and some began to look with suspicion on those who had married "foreign wives." (In the companion book of Nehemiah, 13:1 cites Deuteronomy 23:3-6 and its ban on Moabites and Ammonites from the assembly of Yahweh.) Eventually Ezra, in today's Old Testament lectionary reading, orders the people, "Separate yourselves from the peoples of the land and from the foreign wives." That likely would be a death sentence to many women and children, but God demands purity.

Interestingly, the Old Testament has another book that takes an entirely different point of view. The title character in the book of Ruth is a Moabite, and the great-grandmother of King David no less. If Ezra's rule had been enforced in her time, David might never have existed. The story of Ruth lifts up a Moabite woman as a paragon of virtue and faithfulness. She is a "foreign wife" like those Ezra banishes in the name of the purity God demands.

There is a good bit of worry and fear associated with foreigners in our day. Some are terrified of the threat posed by Syrian refugees, and quite a few governors have declared they want no refugees in their states. The issue is not religious purity, though some have proposed letting in only Christian refugees. But in both our day and Ezra's, the foreigner is viewed as a danger. And when people think they are in danger, they often act is ways they later regret. Whether Ezra later did so in unknown, but the book of Ruth and the teachings of Jesus certainly repudiate Ezra's actions.

In the New Testament epistle of 1 John, we find the famous line, "Whoever does not know love does not know God, for God is love." And just a few verses later it adds, "There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear." My love certainly isn't perfect, and so I have my share of fears, but when my actions are driven primarily by such fears, it seems highly likely that I will be acting in ways contrary to those of the God who "is love."

Like Ezra, I can always find a verse of Scripture to justify my actions when I am afraid, but I'm pretty sure that means I'm reading my Bible incorrectly.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Naturally there were people who looked for something or someone to blame. Perhaps they weren't pure enough to please God, and some began to look with suspicion on those who had married "foreign wives." (In the companion book of Nehemiah, 13:1 cites Deuteronomy 23:3-6 and its ban on Moabites and Ammonites from the assembly of Yahweh.) Eventually Ezra, in today's Old Testament lectionary reading, orders the people, "Separate yourselves from the peoples of the land and from the foreign wives." That likely would be a death sentence to many women and children, but God demands purity.

Interestingly, the Old Testament has another book that takes an entirely different point of view. The title character in the book of Ruth is a Moabite, and the great-grandmother of King David no less. If Ezra's rule had been enforced in her time, David might never have existed. The story of Ruth lifts up a Moabite woman as a paragon of virtue and faithfulness. She is a "foreign wife" like those Ezra banishes in the name of the purity God demands.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

There is a good bit of worry and fear associated with foreigners in our day. Some are terrified of the threat posed by Syrian refugees, and quite a few governors have declared they want no refugees in their states. The issue is not religious purity, though some have proposed letting in only Christian refugees. But in both our day and Ezra's, the foreigner is viewed as a danger. And when people think they are in danger, they often act is ways they later regret. Whether Ezra later did so in unknown, but the book of Ruth and the teachings of Jesus certainly repudiate Ezra's actions.

In the New Testament epistle of 1 John, we find the famous line, "Whoever does not know love does not know God, for God is love." And just a few verses later it adds, "There is no fear in love, but perfect love casts out fear." My love certainly isn't perfect, and so I have my share of fears, but when my actions are driven primarily by such fears, it seems highly likely that I will be acting in ways contrary to those of the God who "is love."

Like Ezra, I can always find a verse of Scripture to justify my actions when I am afraid, but I'm pretty sure that means I'm reading my Bible incorrectly.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Monday, November 16, 2015

Sunday, November 15, 2015

Sermon: Forgetting, Remembering, and Waiting for God

1 Samuel 1:4-20

Forgetting, Remembering, and Waiting for God

James Sledge November

15, 2015

Hannah’s

story is a personal one, but it is not just about her. She lives in a time when

Israel is in disarray and chaos, fragmented into tribes that sometimes fight

one another, threatened by the powerful Philistines. The hope and promise from

the days of Moses and Joshua are gone. Hannah’s personal despair mirrors that

of Israel.

Hannah

despairs because she is childless, something understood as a curse from God. Yahweh

had closed her womb, the story tells us twice. God, it seems, is Hannah’s

enemy.

Hannah

lived in a patriarchal society where the value of women was largely limited to

child bearing and nurture. A woman who could not have children had little in

the way of other options for a fulfilling life, and her husband’s other wife

never let Hannah forget that. She tormented her, a pain only intensified by the

annual trips to Shiloh where each family member offered sacrifices at the

sanctuary of God. Sacrifices to the one who had cursed her.

Her

husband Elkanah loves her and doesn’t

think her worthless, but his efforts to cheer her up fall a little flat. “Why

are you so sad? Why won’t you eat? After all, you have me.” Even I know better

than that, and my wife says I’m clueless.

Elkanah

isn’t the only clueless guy in the story. Eli the priest stumbles badly

himself. He’s there in the temple when Hannah comes in, walking right past him.

She makes no notice of the priest, taking her case straight to Yahweh. She has

a bitter complaint. God has forgotten her, and she longs to be remembered.

Eli

totally misreads her, thinking she’s drunk because she moves her lips without

speaking. That seems pretty thin evidence. Maybe he’s not used to women barging

right by him and dropping on the floor before God.

Hannah

quickly sets the priest straight, but then adds, “Do not regard your servant as a worthless

woman…” That is the problem. In her world, she is considered cursed and

worthless.

I’m

not certain how to read Eli’s response. He does seem sympathetic, but when he

says, “the God of Israel grant the petition you have made…” is that a

promise, or merely a hope? However Eli means it, Hannah goes home glad.

I occasionally have someone share a crisis

with me and ask me to pray for her. I’m happy to do so, and I hope my prayers

provide some comfort. Still, I don’t know that either of us thinks the

situation changed after I’m finished. I’m not sure anyone goes home glad.

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

Church Newsletter for Advent

Our congregation produces a quarterly newsletter. Here is my upcoming piece for the Winter edition.

Sisters and Brothers in Christ,

As I write this it is a

beautiful, autumn day. Some trees still cling to brightly colored leaves.

Thanksgiving is still two weeks away, but one of my neighbors already has up

his Christmas lights. And we’ve had the first salvo in the annual “War on

Christmas” silliness, thanks to those atheists

at Starbucks who removed the snowflakes, those ancient symbols of

Christ’s birth, from their seasonal cups.

I’m not much bothered by early

Christmas decorations, or by what retailers put on their cups or store

decorations. I’m not offended if the stores are already playing Christmas music.

Surprised and amused, perhaps, but not much more. I do, however, sometimes lament

the loss of Advent. I don’t suppose that stores or malls ever did Advent, but I

do miss it when it fades away in churches.

The Presbyterian Book of Common Worship has a liturgy for

lighting the Advent candle on the four Sundays prior to Christmas. It begins, “We

light this candle as a sign of the coming light of Christ. Advent means coming.

We are preparing ourselves for the days when…” What follows is a list of that grows longer each week and speaks of swords beaten into plowshares, nations

no longer learning war, wolves making peace with lambs, the desert blooming, and

a young woman who bears a child named “God with us.”

“Advent means coming.” It’s a coming

that is not of our making. We can prepare. We can work to make it more visible,

but only God can bring the promise. That means that Advent is also about

waiting.

I am not very good at waiting. I’m

impatient and sometimes impulsive. I’m even worse at waiting for God. I am very

much a product of our culture that values busyness and productivity. But God’s

ways are very different from mine, and over the years I’ve discovered that a

deep experience of God requires prayer and stillness and silence and waiting.

Advent requires waiting. It is

an active, expectant sort of waiting, but it is waiting nonetheless. Yet too

often we rush toward Christmas, trying to manufacture joy and cheer, trying to

make Advent into one long and extended Christmas celebration.

I’m not suggesting that we

should be dour and somber until Christmas Eve, or that we hold all the

Christmas carols in reserve until that day. (I would prefer we not pack up the

carols so quickly after Christmas.) I

do, however, think it important to cultivate the spiritual disciplines of

waiting and of preparing for what God will do. Expectant and faithful waiting

that trusts in God’s promises is crucial to living as the body of Christ in

Advent and throughout the year.

Some years ago John Buchanan,

then pastor at Fourth Presbyterian in Chicago and editor of The Christian Century, wrote a piece

entitled “Deepening Darkness.” In it he described the busyness of the holidays on

the Magnificent Mile portion of Michigan Avenue where the church sits. “The

sidewalks are filled with shoppers. Buses arrive daily from the suburbs and

nearby states, disgorge their shoppers in the morning and pick them up,

exhausted and heavily laden, in the evening. We sit in the middle of it all

with the somber purple color and sing hymns in a minor key.” (The Christian Century, 11-28-2006)

I wonder what sort of witness a faithful

observance of Advent might offer to our busy, hectic and anxious world.

Grace, peace, a blessed Advent,

and a Joyous Christmas,

Monday, November 9, 2015

Sunday, November 8, 2015

Sermon: Bad Ole Moabites and Wrestling with Scripture

Ruth 3:1-5; 4:13-17

Bad Ole Moabites and Wrestling with Scripture

James Sledge November

8, 2015

The

Old Testament book of Deuteronomy shows Moses reminding Israel, just prior to

their entering the land of promise, of all the covenantal requirements and

obligations of the Law. Moses will not enter the land with them, and this is

his final act before handing leadership of Israel over to Joshua. Here is part

of what he says. “No Ammonite or Moabite shall be admitted to the assembly of the Lord. Even to the tenth generation, none

of their descendants shall be admitted…”

Now

if you’re worried that I’ve gotten confused about the scripture readings for

today, let me assure you that this has everything to do with Ruth. But to make

that clear, we probably need to go back to the beginning of her and Naomi’s story.

As

the story opens, there is a famine in Israel causing Naomi, her husband, and

two sons to flee their homeland. They become refugees, not so different from Syrian

refugees in our day. They are in danger and at the mercy of those they

encounter. And in the case of Naomi’s family, they end up in the land of those

bad ole Moabites Moses warned them about.

The

story doesn’t share any details of what happen when Naomi’s clan arrives in

Moab. But clearly they are allowed to settle there. They are able to make a

life, and when her husband dies, Naomi’s family is sufficiently a part of the

community that her sons are welcomed to marry two of the local girls, Orpah and

Ruth.

But

then the situation changes dramatically. Naomi’s two sons die. I’m not sure we

modern people can fully appreciate what a dire situation this is. As a widow

without male children, Naomi was in grave jeopardy. She was too old to be

married again, and she had no one to provide for her. As a woman, she could not

inherit or own property. With no husband, no sons, and no grandsons, her

husband’s lineage was at an end, and she was powerless and destitute.

Then

Naomi learns that the famine in Israel has abated. This does not offer much

hope, but it is all she has. She heads back hoping some relatives or friends will

take pity on her. She may still be destitute, but it seems the best chance she

has. And so she starts out for home, her daughters-in-law accompanying her. But

Naomi knows this is not a good idea.

Naomi

has no way to provide for herself, much less for Orpah and Ruth. They are still

relatively young. If they return to their own families, perhaps they will care

for them, even find new husbands for them. Orpah and Ruth protest. They want to

remain with Naomi. But she insists, and finally Orpah relents and leaves,

weeping as she goes.

But

Ruth will not leave. She casts her lot with Naomi, and they return to the land

of Judah and to poverty. Ruth is now the refugee, dependent on the hospitality

of strangers. She tries to help Naomi by gleaning, picking up the grain that gets

dropped during the harvest.

The

story of Ruth is one of several in the Old Testament where God’s name is

mentioned and invoked but God does not seem to be an actor in the story. Which

is not to say that God is not at work. Ruth goes to glean in the fields and by

“chance,” ends up in the field of Boaz, a relative of her long dead

father-in-law.

Boaz

does not recognize this refugee gleaning in his field, and so he asks who she

is. No one seems to know her name. She’s just a refugee, after all. They tell

him, She

is the Moabite who came back with Naomi from the country of Moab. I’m

not sure why they need to say she’s a Moabite from Moab. That’s like saying,

“I’m an American from America.” But it does make perfectly clear that she is

one of those bad ole Moabites.

When Naomi and her family fled to Moab,

their survival depended largely on whether they encountered hostility or

hospitality there. Now Naomi and Ruth’s survival depend largely on whether Ruth

encounters hostility or hospitality from the people of Judah, and especially

from Boaz. God’s providence has steered Ruth to the field belonging to a

relative of Naomi’s husband, but we know nothing of him or what he thinks about

hungry refugees or bad ole Moabites. At least we don’t until he gives his

workers special instructions to look after Ruth, praises her for her care of

Naomi, and gives her food and drink.

Sunday, October 25, 2015

Sermon: Miraculously Healed by Jesus

Mark 10:46-25

Miraculously Healed by Jesus

James Sledge October

25, 2015

I

came across a story recently that’s a bit lame, or worse than that, but I think

I’ll share it anyway. A farmer lived along a quiet, county road, but over the

years, it became a busy highway, and the speeding cars began to kill more and

more of the farmer’s free-range chickens.

He

called the local sheriff to complain. “You’ve got to do something to slow these

cars down,” he said. “They’re driving like mad men.” The sheriff wasn’t sure

there was much he could do, but after repeated calls from the farmer then he agreed

to put up a sign that might make people more attentive. It said, “SLOW: SCHOOL

CROSSING.”

But

a few days later the farmer called to say that the sign hadn’t worked at all.

If anything, the drivers seem to have sped up. So the sheriff tried a slightly

different tactic, installing a sign that said “SLOW: CHILDREN AT PLAY.” And the

cars went even faster.

Finally,

the exasperated farmer asked if he could put up his own sign. The sheriff was

tired of the farmer calling every day, so he agreed, and the calls stopped. Eventually

the sheriff decided to call and check on things. The farmer said he hadn’t lost

a chicken since he put up his sign. The sheriff had to see this, so he drove

out to the farm where he saw a piece of plywood with spray-painted wording that

said, “NUDIST COLONY: Go slow and watch out for the chicks!”[1] …I told you it was bad.

I

told this story, lame as it is, to raise the issue of what it takes to get folks

to slow down and pay attention. We live in a fast paced world where we are

often busy and overscheduled. It’s a threat to our mental health and overall

well-being, and that of our children. Even more, it is a huge threat to a

relationship with God, to getting to know Jesus, because that requires

stopping, waiting, silence, and attentiveness on our part.

But

lest you think this a peculiarly modern problem, the people in our gospel

reading also seem unable to slow down enough to see what truly is important.

Jesus has just passed through Jericho. Jerusalem is not very far away, and the

very next episode in Mark’s gospel is Jesus’ triumphal entry into the city of

David. Jesus is picking up something of an entourage. He, his disciples, and a

large crowd are all headed down the road when a blind beggar begins to cry out.

“Jesus,

Son of David, have mercy on me!”

The

beggar’s name is Bartimaeus… or perhaps not. Our story says he is Bartimaeus,

son of Timaeus, but Bartimeaus means son of Timaeus. I’m suspicious that Mark’s

gospel gives us the original Aramaic and then its translation. This blind

beggar is insignificant enough that no one remembers his name, only that of his

father.

An

unnamed, blind beggar is hardly important enough to warrant stopping,

especially for this procession headed to big events in Jerusalem. “We’ve got to

keep moving. Be quiet!” blind beggar. We’ve got somewhere to be.”

Our

readings says, Many sternly ordered him to be quiet. Many? Many of the

disciples? Many in the crowd? Many of both? The last time anyone spoke in this

stern manner it was the disciples trying to chase away those bringing children

to Jesus. Unimportant children, now an unimportant, blind beggar. “Shoo, get

away. No time for you.”

In one of those wonderful ironies of

Scripture, the blind man sees what the crowd and disciples cannot. Jesus came

for people such as this blind beggar, and he came to help people see. Jesus

heals the beggar’s blindness with little difficulty. But the harder work of

healing his followers’ blindness continues and won’t come to full fruition

until after the resurrection and the gift of the Holy Spirit.

Tuesday, October 20, 2015

Monday, October 19, 2015

Peace, Unity, and Purity... and Other Impossible Combinations

Steadfast love and faithfulness will meet;

righteousness and peace will kiss each other.

Faithfulness will spring up from the ground,

and righteousness will look down from the sky.

righteousness and peace will kiss each other.

Faithfulness will spring up from the ground,

and righteousness will look down from the sky.

Psalm 85:10-11

I've always loved these lines from Psalm 85, one of today's evening psalms. The psalm itself is a plea for God to restore, a prayer based in knowledge of God's nature and character. And so, even in the midst of difficult circumstances, the psalmists hopes for the wondrous day when "righteousness and peace will kiss each other."

God is often seen as having contradictory, almost incompatible attributes. God is a God of justice, who will not tolerate wickedness. God is a God of mercy and forgiveness, who in Jesus is a friend of sinners and tax collectors. A lot of people prefer one or the other of these images, and this, in part, accounts for some of the wildly different versions of Christianity floating around.

The psalmist is aware of both images, asking earlier in his prayer, "Will you be angry with us forever?" Presumably there is some reason for God to be angry. Israel has not lived as God has commanded. They in some way deserve the judgment they are experiencing, and yet the psalmist can cry out, "Grant us your salvation."

The psalmist hopes for righteousness and peace to kiss, but just how compatible are such things? Righteousness is about doing things correctly, about abiding by God's law. Does the psalmist simply mean that peace will emerge when people live rightly, or is there a hope that God's justice and love can coexist?

When Presbyterian elders, deacons, and pastors are ordained, one of the vows we make is to further the "peace, unity, and purity of the Church." It sounds lovely, but it is remarkably difficult to put into practice. Purity, like righteousness, is about doing things correctly, about living according to God's will. Peace and unity often seem to require some negotiating and compromise with purity. In the end, many congregations end up leaning one way of the other, some focused more on holy living and others focused more on loving each other and getting along. I'm not sure that either move looks very much like the psalmist's dream of a day when "righteousness and peace will kiss one another."

Perhaps we humans can never fully reconcile righteousness and peace, judgment and forgiveness, but does that mean God is bound by our limitation on this? People of faith speak of imaging God, of being the body of Christ. Surely that means that we are to move toward what God is like rather expecting God to be like us.

I suspect that most people who are serious about faith have a pretty good idea which image of God they prefer. And that means we already know about that side of God that unnerves us, that image of God we need to learn to embrace, even kiss.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Sunday, October 18, 2015

Sermon: Radically Dissimilar Hearts

Mark 10:35-45

Radically Dissimilar Hearts

James Sledge October

18, 2015

Our

gospel reading this morning would probably benefit from a bit of context. It

takes place shortly after Jesus’ encounter with a rich man who works hard to

keep God’s commandments yet feels there must be something more. But Jesus’ call

to sell what he owns, give the money to the poor, and become a disciple, is too

much.

Then

Jesus and his followers hit the road again, headed to Jerusalem. The disciples

don’t come off all that well in Mark’s gospel, repeatedly misunderstanding what

Jesus teaches. But that is not to say that they are total idiots. They have

clearly begun to grasp that danger lies ahead. The gospel says that as Jesus

walks ahead of them, They were amazed, and those who followed

were afraid. To these amazed and frightened followers, Jesus explains

for a third and final time what will happen to him in just over a week.

Then

James and John come to see him. Their request seems the epitome of the

disciples’ cluelessness. James and John, along with Peter, form Jesus’ inner circle,

a privileged trio who’ve seen things the others have not. Now they take

advantage of this. They appear to realize there is something unseemly in their

request, but they make it anyway.

But

perhaps this is not merely arrogance or an attempt to turn their inside

connection into special favors. What if this is simply two terrified followers

trying to save their own skin? They’ve started to understand that this trip to

Jerusalem is not going to end well. Jesus is not going to overthrow the Romans.

In fact he keeps saying people will kill him. In some ways it’s amazing that

the disciples stay with him as he leads them toward Jerusalem and the cross.

Maybe because they’ve followed him this

far, they decide to see it through. Maybe because he keeps talking about rising

again, they hope there might be something beyond the horrible events that await.

If there really is something after Jerusalem, maybe they can be part of it. “Grant

us to sit, one at your right hand and one at your left, in your glory.”

Monday, October 5, 2015

"The Other" and Christian Witness

"All things are lawful,” but not all things are beneficial. “All things are lawful,” but not all things build up. Do not seek your own advantage, but that of the other.

"All things are lawful,” but not all things are beneficial. “All things are lawful,” but not all things build up. Do not seek your own advantage, but that of the other.

1 Corinthians 10:23-24

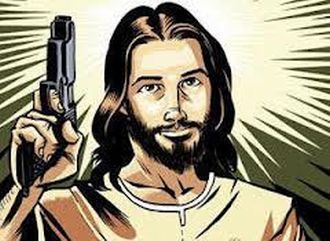

I read on The Washington Post website today where Tennessee Lt. Gov. Ron Ramsey suggested that devout Christians "should think about getting a handgun permit." This was in reaction to the shooting at an Oregon community college where the shooter seemed to target Christians.

I can understand why Christians who already are worried about the faith's place in our culture would be further unnerved by an act of violence aimed specifically at Christians (an experience other faiths know all too well). But I wonder what sort of Christian witness would be given if a gunman walked into a crowded venue and all the Christians whipped out their pistols and mowed him down.

St. Augustine long ago wrote that Christians might engage in violence and even deadly force to save another, but never to save themselves. His thought led to what is usually called "just war" theory, the idea that there are times when violence is required of those who follow the Christ who gives his own life and tells his followers to emulate him. But in such thinking, violence can never be for mere self preservation. It must be done in an act of loving the other. Just war or violence is an agonized choice to injure one in order to save others.

Americans have a tendency to understand freedom in terms of a lack of restraints on what I want to do. I'm all for this sort of freedom - up to a point - but that is not the sort of freedom Paul or Jesus speak of in the New Testament. For them, freedom releases us from an overly selfish or narrow viewpoint, allowing us to love others more fully. Jesus goes so far as to include the enemy in the orbit of one's love and concern. This sort of freedom allows people to become Christ-like, living for God and others more than self.

You can see that in Paul's words from today's epistle. Paul's Corinthian congregation has embraced their new freedom in Christ, but they've misunderstood it in libertine and individualistic ways. Paul corrects them and reminds them that their freedom is always in service to "the other."

The American Church and body politic would both do well to listen to Paul. Both have become overly individualistic, concerned narrowly for self and those who agree with me. Add in the climate of fear which seem so pervasive these days, and "the other" is more likely to become the object of my derision or much worse than the one whose good I seek.

In the Greek language used to write the New Testament, the word translated "witness" is the root of our word "martyr." The connection of these two terms came from the way many early heroes of the faith, including its founder, maintained their faith even in the face of death. Surely there was the occasional Christian of that time who chose to pull out his sword and make a stand, but not one of them is lifted up in the Bible or early Church writings.

I do wish that someone had been able to stop the Oregon shooter. (We need genuine dialogue about the best ways to prevents such acts in the future, but unfortunately we are largely divided into political camps who spout talking points at one another.) But I will not be encouraging anyone to buy a weapon for self-defense. Christians are called to be the body of Christ, and for the life of me, I cannot picture the Jesus we meet in the Bible packing a gun.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

I can understand why Christians who already are worried about the faith's place in our culture would be further unnerved by an act of violence aimed specifically at Christians (an experience other faiths know all too well). But I wonder what sort of Christian witness would be given if a gunman walked into a crowded venue and all the Christians whipped out their pistols and mowed him down.

St. Augustine long ago wrote that Christians might engage in violence and even deadly force to save another, but never to save themselves. His thought led to what is usually called "just war" theory, the idea that there are times when violence is required of those who follow the Christ who gives his own life and tells his followers to emulate him. But in such thinking, violence can never be for mere self preservation. It must be done in an act of loving the other. Just war or violence is an agonized choice to injure one in order to save others.

************************************************

Americans have a tendency to understand freedom in terms of a lack of restraints on what I want to do. I'm all for this sort of freedom - up to a point - but that is not the sort of freedom Paul or Jesus speak of in the New Testament. For them, freedom releases us from an overly selfish or narrow viewpoint, allowing us to love others more fully. Jesus goes so far as to include the enemy in the orbit of one's love and concern. This sort of freedom allows people to become Christ-like, living for God and others more than self.

You can see that in Paul's words from today's epistle. Paul's Corinthian congregation has embraced their new freedom in Christ, but they've misunderstood it in libertine and individualistic ways. Paul corrects them and reminds them that their freedom is always in service to "the other."

The American Church and body politic would both do well to listen to Paul. Both have become overly individualistic, concerned narrowly for self and those who agree with me. Add in the climate of fear which seem so pervasive these days, and "the other" is more likely to become the object of my derision or much worse than the one whose good I seek.

In the Greek language used to write the New Testament, the word translated "witness" is the root of our word "martyr." The connection of these two terms came from the way many early heroes of the faith, including its founder, maintained their faith even in the face of death. Surely there was the occasional Christian of that time who chose to pull out his sword and make a stand, but not one of them is lifted up in the Bible or early Church writings.

I do wish that someone had been able to stop the Oregon shooter. (We need genuine dialogue about the best ways to prevents such acts in the future, but unfortunately we are largely divided into political camps who spout talking points at one another.) But I will not be encouraging anyone to buy a weapon for self-defense. Christians are called to be the body of Christ, and for the life of me, I cannot picture the Jesus we meet in the Bible packing a gun.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Sunday, October 4, 2015

Sermon: No Tokens Required

Mark 10:2-16

No Tokens Required

James Sledge October 4,

2015

If

you go into our church parlor, you will find a few items from this

congregation’s history displayed there. There’s an old pulpit Bible and a curio

cabinet with an old hymnal, more Bibles, old photos, and other artifacts. Young

congregations tend not to have such displays, but those that have been around long

enough often have a history display somewhere.

I

once visited an old church with an elaborate display going back to colonial days.

And in one corner of this mini-museum, on a curio shelf, were some communion

tokens.

If

you’ve never heard of such things, they are just what the name implies, tokens

that gained a person admission to the Lord’s Supper. They were used back in the

days of very infrequent communion, and you got one after elders from the Session

(our church governing council) visited and quizzed you about your understanding

of the faith. John Calvin suggested such a practice to ensure that people

correctly understood the sacrament. He worried about what he saw as magical or

superstitious beliefs about the Lord’s Supper.

Calvin

may have understood these tokens as a kind of impromptu communicants’ class

rather than a gauge of personal worthiness, but even if he did, you can be sure

that people were denied tokens for reasons other than insufficient

understanding of Reformed theology. Inevitably, the elders made character

judgments about church members and denied tokens to those who didn’t measure

up.

Use of these tokens largely disappeared

in the 1800s, but it’s interesting to wonder about what sort of moral failing

would have prevented people receiving one. Could a young, unmarried woman with

a child get one? How about those who were divorced? What about drinking or

carousing or dancing? Tokens were done on a church by church basis, so there

was likely a good deal of variety from place to place. Nonetheless I feel

confident that there were plenty of congregations that would not have welcomed divorced

folks to the table.

___________________________________________________________________________

“Truly

I tell you, whoever does not receive the kingdom of God as a little child will

never enter it.” When

the gospel of Mark wants to take up an entirely new topic, the writer will

often change locales, but he tells us about people bringing little children to

Jesus with no break at all from the teachings on marriage. Curious.

Jesus

has just finished talking about how relationships would work if people’s hearts

weren’t out of whack, when the disciples demonstrate, for the umpteenth time,

that they still don’t get this kingdom thing. Turn back one page in Mark’s

gospel and you’ll hear Jesus saying, “Whoever welcomes one such child in my name

welcomes me.” He has already said that children in some way exemplify what

it means to be highly valued in the kingdom’s way of viewing things, but these

disciples are fairly slow learners, like disciples in every age.

This

seems to be the only place in Mark’s gospel where we’re explicitly told that Jesus

got mad at his followers, “indignant” our translation says. Surely there is

some significance here. Surely we are being told to pay attention.

Thursday, October 1, 2015

Not again!

It happened again today - a shooting at a school. Current reports say 10 may have been killed at an Oregon community college in the 145th school shooting since Sandy Hook. Such a number - 145 - should make even the most ardent gun collector or avid shooter say, "Something is terribly wrong."

It happened again today - a shooting at a school. Current reports say 10 may have been killed at an Oregon community college in the 145th school shooting since Sandy Hook. Such a number - 145 - should make even the most ardent gun collector or avid shooter say, "Something is terribly wrong."Recently some of my "friends" on Facebook have shared a pro-gun post that talks about how Switzerland encourages gun ownership, having one of the higher rates of gun ownership in the world, and yet has one of the lower murder rates. What the post conveniently leaves out is how regulated this ownership is, with required classes and registration. There is even a regulatory process one must follow to buy ammunition, with certain types banned. But those who tout Switzerland as an example of why it is good to own guns usually insist that any regulation or registration regarding guns infringes on their rights.

Obsessing about "my rights" is a popular American pastime, one not restricted to any political persuasion. But in the case of rights related to guns, my Facebook "friends" who seem obsessed with such rights are very often the same "friends" who regularly share posts encouraging people to "share this picture of Jesus" or do some other act that confirms their faith. Yet the Jesus of whom they speak calls his followers to willingly let go of their own good, their own rights, for the sake of others.

I never cease to be amazed at the human capacity to link personal preferences, beliefs, biases, etc. to one's faith, even when the founder of that faith speaks in ways completely counter to such preferences, beliefs, and so on. And so Jesus, the pacifist Messiah ends up being pro-military, pro-self defense, and pro-gun. The Christ who speaks of wealth and greed as huge barriers to life in God's coming kingdom ends up wanting you to be successful and rich. And the Jesus who calls on a rich man to sell all he has and give the proceeds to the poor would never ask that of me.

Almost all people who call themselves Christian have ways of distorting faith to make it line up with their wants and desires. It is a sin where we all need to repent. But right now, at this point in our life together as Americans, there is a terrible and pressing need for gun enthusiasts who call themselves Christian to repent and say, I am willing to deny myself, to give up my rights, to do whatever it takes to safeguard the lives of school children and innocents everywhere.

Either that, or stop with the Jesus Facebook posts.

Monday, September 28, 2015

What Me Worry?

"Therefore I tell you, do not worry about your life, what you will eat or what you will drink, or about your body, what you will wear. "

Matthew 6:25

I wonder if telling someone not to worry has ever stopped that person from worrying. Jesus clearly thinks that worrying is a problem for living the life he teached, the way he calls Christians to walk. Yet we Christians sure do a lot of worrying. (We're also accomplished at fear, another thing that runs counter to the way of Jesus.)

Not that we have no reasons for worrying. Most American denominations are experiencing significant numerical decline. Congregations worry about budgets and where to cut if this year's stewardship campaign disappoints. Sports leagues and a plethora of other activities are scheduled at times once reserved for church activities. Who wouldn't worry?

Right this moment I'm doing a mental inventory of the big items on my worry list. They are a mix of the personal and the professional, which in my case has to do with church. I have the run of the mill concerns shared with many others. Is there enough money for everything? Did we pay too much for our house? Will we get enough when it comes time to sell it? Will the crazies in Congress cause another sequestration and accidentally send the economy over the edge, and the DC area housing market with it? What will this mean when it finally comes time to retire?

On the professional/church front, our stewardship campaign is just starting, and I'd be lying if I said I had no worries regarding it. Like many churches, we are disproportionately dependent on a handful of bigger givers. What if one moves or simply decides to give a lot less? And will we find the right person to fill that open staff position? And what will happen to the program if we don't? In the meantime, am I doing what I should be, or am I going about things all wrong? Do I need to learn some new trick or get a lot better at some facet of my ministry if things are to go well? There is plenty to worry about.

At the same time, I wonder how many of my worries have even the tiniest thing to do with Jesus or the the new day (kingdom) he calls people to be a part of. Jesus taught his followers to pray for "daily bread" so the sort of security he promises may have little to do with getting a good return on my housing "investment." Actually, when I reflect on Jesus' priorities, it does often help with my worries. As I think more about a different set of priorities from those that sometimes drive me, it often has a calming effect

But what about church? Church is all about Jesus, all about God's new day, and so if I'm worried about Church then my worries are of a deeper and more troubling sort (with a personal, financial component added in because the church writes my paycheck). Except that the Church is often about all manner of things having little to do with Jesus or God's new day.

Yesterday during worship, Kerry, one of the elders who serve as the spiritual leaders of our congregation, gave a wonderful, brief "stewardship moment." In it she shared a quote from Pope Francis. “I prefer a church which is bruised, hurting and dirty because it has been out on the streets, rather than a church which is unhealthy from being confined and from clinging to its own security."

Very often my worries about Church are worries about security. They are not concerns over how faithful we are being to Christ's call, or worries about whether Jesus wants us to do this as opposed to that. Buildings and classes and music programs and youth group may be related to our call to be Christ in and for the world, but they also can easily become things that distract us from that work. They can be the very things that keep us focused on our own security rather than our call to risky work out on the streets.

I suspect that church professionals such as myself can be especially prone to such temptations. I also suspect that many of us are good at absolving ourselves and blaming our congregations for this problem. I wonder what might happen if pastors and congregations could together listen to Jesus, stop worrying for a moment, and take a good look at our priorities. If we discovered we were worrying about a lot of the wrong things, what might change?

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Sunday, September 27, 2015

Preaching Thoughts on a Non-Preaching Sunday

The prayer of the righteous is

powerful and effective. - James 5:16

As a pastor, I deal regularly in prayer. I lead prayers in worship. At committee meetings, I'm often the one who gets asked to pray. People ask me to pray for them or their loved ones in moments of crisis. Our denomination even requires that all meetings of the church's governing council open and close with prayer. Prayer is clearly a "big deal" in the church.

Prayer is a big deal in the Bible as well. Jesus is frequently shown praying, and the disciples ask for instruction on praying from him. Today's lectionary passage talks about length about prayer. I glanced at a Bible concordance, and it listed hundreds of verses featuring the word "prayer" or forms of the word "pray."

But if prayer is clearly central to the Christian life, it is also problematic. From football teams praying for victory to armies doing the same to people praying for a winning lottery ticket, prayer gets employed for questionable purposes. I once read about a boxer who prayed to win his bout. He explained that after the prayer he could feel the power of God in his fists, pummeling his opponent into submission. Really?

Thoughtful Christians who are uneasy about such prayers have every right to be. The notion that God is some sort of genie who must grant requests offered with the correct formula, or that God can be compelled to act if enough "prayer warriors" fill God's inbox to overflowing, is more than a little troubling. No wonder many Christians become uneasy and hesitant about prayer.

Of course the "prayer of the righteous" refers not to prayer offered the right way but to prayer offered from a right heart, a heart aligned with God. Many popular ideas about prayer are huge distortions of what the Bible actually says. Prayer has never been about getting God to do our bidding or convincing God to see things as I do.

But while prayer is often misunderstood and abused, I'm not sure that is the primary reason it is problematic for some Christians. Recognizing that God won't buy me a new Mercedes Benz just because I want one is not a reason to conclude that God does not respond to prayer. However, if I am convinced that God is distant and removed, never actively engaged in human life of history, then prayer may indeed seem unnecessary and even a waste of time. If God is not very real, why bother to pray?

If as Christians, we are bothered by the way prayer is trivialized and abused, treated it like asking Santa for goodies, then it will serve us well to develop a deeper understanding of prayer. As we learn about contemplative prayer, centering prayer, prayer that seeks to draw closer to God, prayer that listens more than it speaks, prayer that seeks Christ's call and the strength to live out that call... our prayer lives will become more central to our faith just as Jesus' was to his, and we will become models of prayer for others.

And if we are Christians who wonder about prayer because we have difficulty imagining that they "do" anything, then it will serve to an even greater degree to develop a deeper understanding of prayer. As we learn about contemplative prayer, centering prayer, prayer that seeks to draw closer to God, prayer that listens more than it speaks, prayer that seeks Christ's call and the strength to live out that call... God and Christ will become more present and more real to us, and we will learn about the power of God at work in our lives, and in the world.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

As a pastor, I deal regularly in prayer. I lead prayers in worship. At committee meetings, I'm often the one who gets asked to pray. People ask me to pray for them or their loved ones in moments of crisis. Our denomination even requires that all meetings of the church's governing council open and close with prayer. Prayer is clearly a "big deal" in the church.

Prayer is a big deal in the Bible as well. Jesus is frequently shown praying, and the disciples ask for instruction on praying from him. Today's lectionary passage talks about length about prayer. I glanced at a Bible concordance, and it listed hundreds of verses featuring the word "prayer" or forms of the word "pray."

But if prayer is clearly central to the Christian life, it is also problematic. From football teams praying for victory to armies doing the same to people praying for a winning lottery ticket, prayer gets employed for questionable purposes. I once read about a boxer who prayed to win his bout. He explained that after the prayer he could feel the power of God in his fists, pummeling his opponent into submission. Really?

Thoughtful Christians who are uneasy about such prayers have every right to be. The notion that God is some sort of genie who must grant requests offered with the correct formula, or that God can be compelled to act if enough "prayer warriors" fill God's inbox to overflowing, is more than a little troubling. No wonder many Christians become uneasy and hesitant about prayer.

Of course the "prayer of the righteous" refers not to prayer offered the right way but to prayer offered from a right heart, a heart aligned with God. Many popular ideas about prayer are huge distortions of what the Bible actually says. Prayer has never been about getting God to do our bidding or convincing God to see things as I do.

But while prayer is often misunderstood and abused, I'm not sure that is the primary reason it is problematic for some Christians. Recognizing that God won't buy me a new Mercedes Benz just because I want one is not a reason to conclude that God does not respond to prayer. However, if I am convinced that God is distant and removed, never actively engaged in human life of history, then prayer may indeed seem unnecessary and even a waste of time. If God is not very real, why bother to pray?

If as Christians, we are bothered by the way prayer is trivialized and abused, treated it like asking Santa for goodies, then it will serve us well to develop a deeper understanding of prayer. As we learn about contemplative prayer, centering prayer, prayer that seeks to draw closer to God, prayer that listens more than it speaks, prayer that seeks Christ's call and the strength to live out that call... our prayer lives will become more central to our faith just as Jesus' was to his, and we will become models of prayer for others.

And if we are Christians who wonder about prayer because we have difficulty imagining that they "do" anything, then it will serve to an even greater degree to develop a deeper understanding of prayer. As we learn about contemplative prayer, centering prayer, prayer that seeks to draw closer to God, prayer that listens more than it speaks, prayer that seeks Christ's call and the strength to live out that call... God and Christ will become more present and more real to us, and we will learn about the power of God at work in our lives, and in the world.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Wednesday, September 23, 2015

The Christ We Show the World

I wrote to you in my letter not to associate with sexually immoral persons — not

at all meaning the immoral of this world, or the greedy and robbers, or

idolaters, since you would then need to go out of the world. But

now I am writing to you not to associate with anyone who bears the name

of brother or sister who is sexually immoral or greedy, or is an

idolater, reviler, drunkard, or robber. Do not even eat with such a one.

Very often we Christians have done the exact opposite of what Paul tells the Corinthians to do. Paul himself seems to worry about being misunderstood. "When I wrote about avoiding immoral folks, I wasn't referring to non-Christians but to church members," he says. Paul expects followers of Jesus to be in the same places Jesus was, among the least and the lost. The good church folks of Jesus' day complained because he hung out with sinners and prostitutes, making the same mistakes many modern Christians make, doing what Paul warned the Corinthians about. Paul expected the community of faith to hold one another to high ethical and moral standards rather than worrying about the morals of those outside the church. But being "the body of Christ" requires the Church to be at work in the same places Jesus was.

We live in a time when fewer and fewer people have more than a passing understanding of what it means to be a disciple, to follow Jesus. A majority of Americans identify as Christian, but large numbers have little familiarity with church, the Bible, or basic tenets of the faith. This means that, increasingly, congregations and individual disciples become the way many people encounter or fail to encounter the living Christ.

I live in the DC metro area, and we are currently being visited by Pope Francis. The adulation of this pope can get a bit overblown at times, but it is easy to see why it happens. (I'm smitten with him at times myself.) He seems to embody what Paul is talking about and what Jesus lives in ways that churches and Christians often do not. His harsh words are for those in power and inside the faith. But he is full of love and concern for those who are struggling: for Syrian refugees, migrants, and the poor, regardless of faith. He is a refreshing view of Christ in a world where Christians often reflect a horrible distorted image of Jesus.

I have a number of Facebook "friends" who regularly post "Christian" memes with a picture of Jesus asking me to share his image if I love him. They post pictures pleading with America to turn back to God and pray for our wayward nation. Then they post angry rants insisting no Syrian refugees should come to America, or threatening to shoot you if you try to take their guns. I wonder what Christ people see in their "witness."

On the flip side are "progressive" Christians who speak of embracing all people in love, who criticize the idea that we can be a "Christian nation" without caring for of those who are poor or hungry or suffering. Then they post blistering personal attacks on Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who refused to give out any marriage licenses rather than give one to a gay couple. They attack her looks, her weight, her personal failings. I wonder what Christ people see in their "witness."

What Christ do people meet through me or you? What Jesus do they encounter through our congregations? These are difficult times for many congregations in the US. Attendance is down; giving is down; our place in the culture is less secure. Churches have a lot to worry about. But I wonder if we don't need to spend a lot more time reflecting on the Christ we reveal to the world.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

1 Corinthians 5:9-11

Very often we Christians have done the exact opposite of what Paul tells the Corinthians to do. Paul himself seems to worry about being misunderstood. "When I wrote about avoiding immoral folks, I wasn't referring to non-Christians but to church members," he says. Paul expects followers of Jesus to be in the same places Jesus was, among the least and the lost. The good church folks of Jesus' day complained because he hung out with sinners and prostitutes, making the same mistakes many modern Christians make, doing what Paul warned the Corinthians about. Paul expected the community of faith to hold one another to high ethical and moral standards rather than worrying about the morals of those outside the church. But being "the body of Christ" requires the Church to be at work in the same places Jesus was.

We live in a time when fewer and fewer people have more than a passing understanding of what it means to be a disciple, to follow Jesus. A majority of Americans identify as Christian, but large numbers have little familiarity with church, the Bible, or basic tenets of the faith. This means that, increasingly, congregations and individual disciples become the way many people encounter or fail to encounter the living Christ.

************************

I live in the DC metro area, and we are currently being visited by Pope Francis. The adulation of this pope can get a bit overblown at times, but it is easy to see why it happens. (I'm smitten with him at times myself.) He seems to embody what Paul is talking about and what Jesus lives in ways that churches and Christians often do not. His harsh words are for those in power and inside the faith. But he is full of love and concern for those who are struggling: for Syrian refugees, migrants, and the poor, regardless of faith. He is a refreshing view of Christ in a world where Christians often reflect a horrible distorted image of Jesus.

I have a number of Facebook "friends" who regularly post "Christian" memes with a picture of Jesus asking me to share his image if I love him. They post pictures pleading with America to turn back to God and pray for our wayward nation. Then they post angry rants insisting no Syrian refugees should come to America, or threatening to shoot you if you try to take their guns. I wonder what Christ people see in their "witness."

On the flip side are "progressive" Christians who speak of embracing all people in love, who criticize the idea that we can be a "Christian nation" without caring for of those who are poor or hungry or suffering. Then they post blistering personal attacks on Kim Davis, the Kentucky county clerk who refused to give out any marriage licenses rather than give one to a gay couple. They attack her looks, her weight, her personal failings. I wonder what Christ people see in their "witness."

What Christ do people meet through me or you? What Jesus do they encounter through our congregations? These are difficult times for many congregations in the US. Attendance is down; giving is down; our place in the culture is less secure. Churches have a lot to worry about. But I wonder if we don't need to spend a lot more time reflecting on the Christ we reveal to the world.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

Monday, September 21, 2015

Sunday, September 20, 2015

Sermon: Long Journey to Something New

Mark 9:30-37

Long Journey to Something New

James Sledge September

20, 2015

How

many of you remember having to write essays or papers in high school or college

of a certain word number? Some of you are no doubt enjoying this experience

right now, and some of our younger worshipers have this to look forward to as

you get a bit older. What word count would you expect for a modest, high school

essay? What about a term paper for a college class? How about a Ph.D.

dissertation? Anyone here who’s done one and can say? Forty or fifty thousand words

sound reasonable?

I

ask because I want us to think for a moment about what is required to cover a

major topic in a fair amount of detail and in a good deal of depth. For

example, if you were going to write something that thoroughly covered what

someone would need to know to live a life of deep Christian faith and

discipleship, how many words would suffice?

Of

course we do have a book that Presbyterians say is the unique and authoritative

witness to Jesus and for life and faith. But if anyone had ever submitted the Bible as a

dissertation or as any other sort of publication, surely some academic advisor

or editor would have quickly returned it saying, “Get back to me when you’ve

done some serious trimming and editing.”

The

Bible weighs in at somewhere near 800,000 words. By comparison, Tolstoy’s War and Peace is a bit over 500,000. If

you were God and wanted to explain this faith thing to folks, don’t you think

you could have come up with a nice pamphlet, or at least something you could

read in a few afternoons? Why on earth have something of this magnitude, a text

that gets squeezed into a single book only because of tiny print and

ridiculously thin sheets of paper?

The

Bible is an unbelievably complex mix of stories and myths and poems and songs

and rules and advice and letters and theology and teachings. Yet we Christians often

examine a few verses here or there and then attempt to distill great theological

truths or axioms from them. I engage is something of this sort most Sundays

when I deliver a sermon rooted in a tiny handful of the Bible’s 800,000 words, 175

words in the case of today’s gospel reading.

Without

some care and restraint, there is a danger of such efforts being akin to carefully

examining the earlobe of the Mona Lisa with a microscope and then proclaiming

to understand the significance of the entire painting.

When

you think about it, the Bible is a strange and wonderful way to make God known

to us, to draw us into relationship with this God. It isn’t a bit of empirical

information to be learned. Rather it is an amazing array of experiences and

stories that share how God has been encountered in a variety of contexts. It is

not unlike getting to know another person, and without understanding context

and circumstances, without knowing to whom certain words were spoken, it is

easy to misconstrue or misunderstand.

Monday, September 14, 2015

Sunday, September 13, 2015

Sermon: Helping Each Other See

Mark 8:27-38

Helping Each Other See

James Sledge September

13, 2015

I’m

going to ask you to imagine a scenario that may terrify some of you. Imagine

that there is someone seated near you that you have never met or seen before.

That’s not the terrifying part… I hope. Worship comes to an end and she turns

to you and says, “I’ve really never done the church thing. Could you tell me

what your church believes about Jesus?”

Let

that sink in for a moment. How would you respond? What would you say to this

person? Really think about it. What would your first words be?

Countless

authors have noted that Mainline Christians, especially those who think of

themselves as more “progressive,” struggle to answer such questions. More often

than not, we instead began to explain what we don’t believe. “We’re not like

that county clerk in Kentucky who won’t give a marriage license to gay couples.

We don’t believe that Jews and Muslims are going to hell. We’re not

fundamentalists who take every word of the Bible literally.” And so on.

Now

some of this may be helpful, even welcome information, but none of it actually

answers her question about what we actually do believe.

In

our gospel reading this morning, Jesus asks a “What do you believe?” sort of

question. He starts with, “What are other folks saying?” Then he moves to, “But

who do you say that I am?” Not so different from someone asking, “What do

you believe about Jesus?”

I wonder how long it took Peter to

answer? Peter seems to be one of those folks who talks first and thinks later,

so I’m betting pretty quickly. I wonder about the other disciples. If Peter had

been quiet for once, what would they have said? Or were they relieved that

Peter had taken the risk and blurted out something?

__________________________________________________________________________

The

gospels were written to help Christians with “What do you believe?” questions,

especially “What do you believe about Jesus?” Because people in our day sometimes

hand out Bibles as a way of introducing Jesus, it’s easy to forget that the

gospels were written, not for people who had yet to hear the story of Jesus, but

for people who already knew it, who were already in a church. They’re written

to help Christians better understand who Jesus is and what difference that is

supposed to make in their lives.

Like

Peter, these folks correctly could identify Jesus. So can most of us. If pressed,

most of us could share a bit of his story, could identify him as Messiah, or

Christ, or Son of God.

But

it turns out that being able to Jesus doesn’t really mean Peter, or any of us,

understand who he is or what it means to follow him. Peter is clearly expecting

a different sort of Messiah than what Jesus describes with his words about

suffering and death, and I’m not so sure that has changed very much in our day.

Probably all of us have ways in which we

would like Jesus to be something or someone other than he says he is. We want

Jesus to help us get where we want to go, but he insists that following him

means letting go of our agendas and connecting to God’s.

Thursday, September 10, 2015

Something More Than Writer's Block

I've not been writing here very much of late. I like to humor myself by imagining that I am a writer, and I've read that genuine writers suffer through times when they cannot find words. I wonder if the term "writer's block" adequately describes that experience. It seems too pedestrian for something that robs a person, however temporarily, of a significant piece of her identity.

My own identity is not much rooted in the musings that show up in this blog, but it is rooted in the faith and spiritual life that lies behind many of my posts. There are times when not writing a blog is simply a matter of too much going on. Some days fill up with events and commitments and activities of a higher priority than blog posts. Still, when my posts become as sporadic as they have in recent months, something more is at work, and "writer's block" feels too pedestrian to describe it.

I read a piece in The Washington Post by Jen Hatmaker where she worried about us pastors. ("How a consumer culture threatens to destroy pastors") Drawing on recent polling data she writes that pastors

When I was in seminary, a pastor nearing retirement shared with me his plan not to darken the door of any church facility upon leaving the pulpit. His best guess was he'd not do church for a year or so. Being an enthusiastic seminary student, I found this strange, bordering on bizarre. Twenty years later, I can better appreciate his plans. Yet I can still get annoyed over church members who don't take their faith "seriously," something generally measured by their level of attendance, giving, or volunteering.

When I encounter a writer's/spiritual block time in my life, I wonder how it would manifest if I were not a professional Christian. (I can't really stop attending on Sundays and still draw a paycheck.) Would I sleep in for a season?

I've frequently heard that non-church folks feel intimidated at the thought of attending worship with church-people who have the faith thing all figured out. They worry that they will stand out and feel lost or out of place. Most church members likely marvel at the idea of their faith intimidating anyone, and I wonder if a similar dynamic might not be at work between many pastors and those in the pews. Perhaps the dynamic is even worse.

Robes and titles and ordination and salary all serve to divide pastors from members, providing means for pastors to hide all those ways that we are a big, human mess. Sometimes members, who pay those salaries, may expect pastors to be "better" Christians than themselves, but the division between pastor and parishioner is detrimental to both. It encourages pastors to keep up an image that is most often far from true, and it robs pastors and parishioners of of the support and companionship they could give one another as they face the inevitable "blocks" that get in the way of full aliveness.

When pastors get together, they sometimes talk, even vent, about their congregations. During full fledged venting, the congregation almost always gets described as "they," or "them." Rarely is it "we" or "us." I would be surprised if church members don't sometimes engage in similar venting about their pastor, with a similar "her and us" or "him and us" divide.

There is something about us humans that looks for a "them" when things are going badly. How different that is from God, who in Christ responds to broken relationship with humanity by becoming fully involved in the pain and suffering of human existence. Strange that we followers of this Christ so often move away from one another when we go through times that challenge, threaten, or frighten us, times when our true selves and identities feel hidden or blocked. Surely Jesus shows us a better way.

My own identity is not much rooted in the musings that show up in this blog, but it is rooted in the faith and spiritual life that lies behind many of my posts. There are times when not writing a blog is simply a matter of too much going on. Some days fill up with events and commitments and activities of a higher priority than blog posts. Still, when my posts become as sporadic as they have in recent months, something more is at work, and "writer's block" feels too pedestrian to describe it.

I read a piece in The Washington Post by Jen Hatmaker where she worried about us pastors. ("How a consumer culture threatens to destroy pastors") Drawing on recent polling data she writes that pastors

suffer in private and struggle in shame: 77 percent of you believe your marriage is unwell, 72 percent only read your Bible when studying for a sermon, 30 percent have had affairs and 70 percent of you are completely lonely.She has a good point. And while I've largely avoided the particular statistics mentioned above, I'm my own sort of mess, one I generally prefer to keep hidden.

You are a mess! Which makes sense because you are human, like every person in your church. You are so incredibly human but afraid to admit it. So few of you do.

When I was in seminary, a pastor nearing retirement shared with me his plan not to darken the door of any church facility upon leaving the pulpit. His best guess was he'd not do church for a year or so. Being an enthusiastic seminary student, I found this strange, bordering on bizarre. Twenty years later, I can better appreciate his plans. Yet I can still get annoyed over church members who don't take their faith "seriously," something generally measured by their level of attendance, giving, or volunteering.

When I encounter a writer's/spiritual block time in my life, I wonder how it would manifest if I were not a professional Christian. (I can't really stop attending on Sundays and still draw a paycheck.) Would I sleep in for a season?

I've frequently heard that non-church folks feel intimidated at the thought of attending worship with church-people who have the faith thing all figured out. They worry that they will stand out and feel lost or out of place. Most church members likely marvel at the idea of their faith intimidating anyone, and I wonder if a similar dynamic might not be at work between many pastors and those in the pews. Perhaps the dynamic is even worse.