This clearly happens when Islamic terrorists believe that they are killing enemies of God rather than fellow humans. The victims are not people with whom terrorists disagree. They are "evil" and less than human because they are God's enemies. Of course such a conclusion requires collapsing God

Deciding that God is exactly as I envision God is clearly an act of creating God in my own image. Such notions are typically referred to as idolatry in Jewish and Christian tradition. I'm no expert in Islamic theology, but I feel reasonably safe in assuming that such behavior is idolatrous for Islam as well. Yet such idolatry seems remarkably popular in our day, and not just with terrorists.

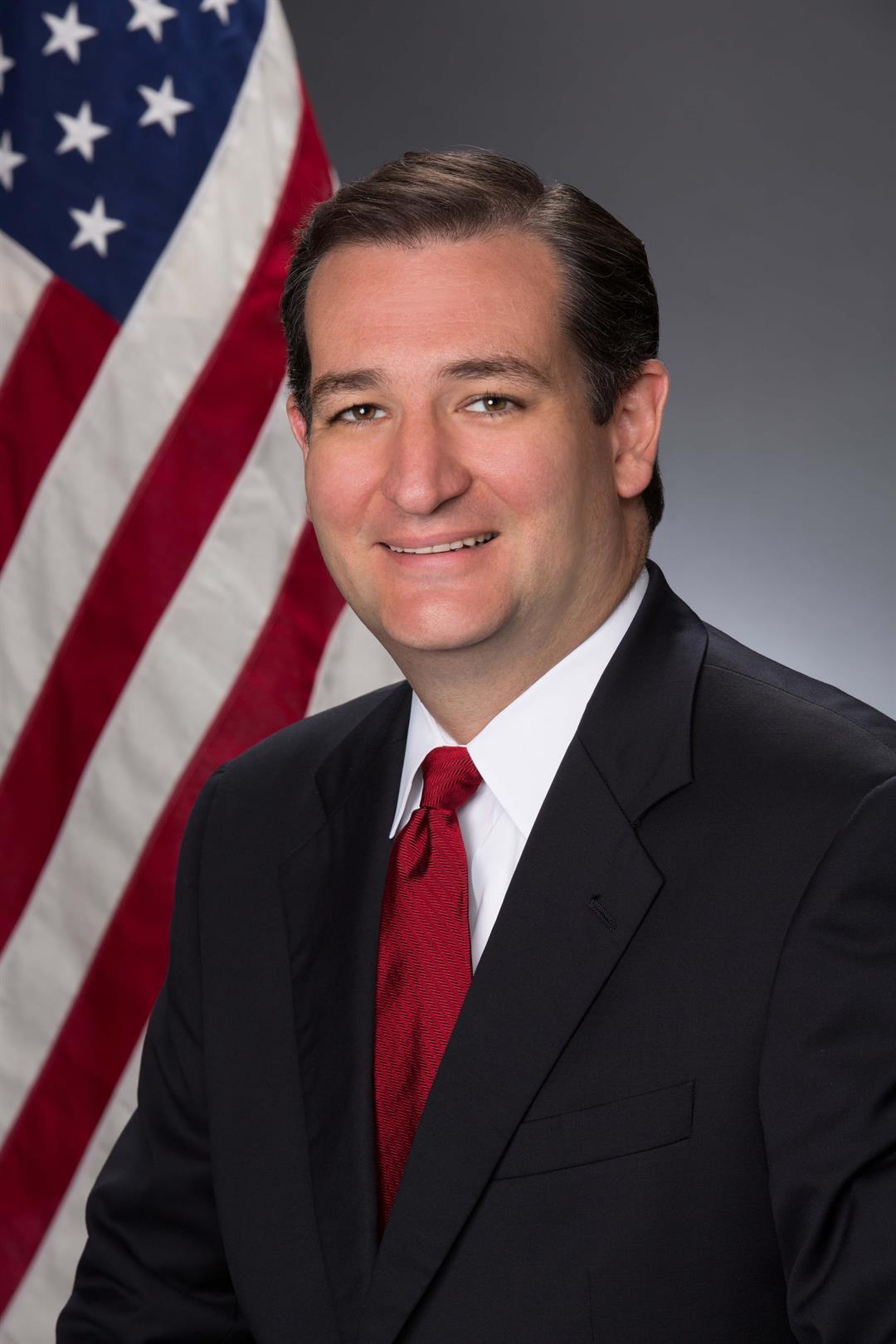

Deciding that God is exactly as I envision God is clearly an act of creating God in my own image. Such notions are typically referred to as idolatry in Jewish and Christian tradition. I'm no expert in Islamic theology, but I feel reasonably safe in assuming that such behavior is idolatrous for Islam as well. Yet such idolatry seems remarkably popular in our day, and not just with terrorists.You see this idolatry in the all too predictable responses to the bombings in Brussels. Ted Cruz called for police to "patrol and secure Muslim neighborhoods" in the US. Donald Trump chimed in that this was a great idea. Cruz surely knows that such actions would be unconstitutional, but he is not speaking of real possibilities. Rather he is appealing to those who view Muslims as God's enemies.

Cruz and quite a few other Christians engage in an idolatry that works very much like that practiced by terrorists. It assumes God and God's view of things is virtually indistinguishable from their views of God and of the world. And while some might object that Cruz and those like him do not advocate bombs in airports or shopping malls, they do advocate torturing people who may be innocent and bombing and killing women and children whose only crime is being related to a terrorist.

Assuming that God favors Americans over others, or even Christians over others, is an idolatrous act that presumes God to be like me. But for Christians at least, the God we meet in Jesus says that loving enemies and praying for those who hurt us makes us more like God. (Matthew 5:43-48) And this same Jesus lifts up a despised, foreign heretic (a Samaritan) as an example of the love for others God demands. (Luke 10:25-37) Thus to insist that we can hate or hurt certain others because we fear them or because they are the "wrong" religion is to refashion God in our image.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

It strikes me that the idolatry of

terrorists and of some reactions to their acts has a parallel in

the bitter political partisanship of our day. It may not be connected

to particular religious traditions. It may even be practiced by

agnostics or atheists, but it follows the same idolatrous pattern. My

view is equated with goodness and righteousness while the views of

others are seen, not as differences of opinion, but as evil. And so

people can speak of those who differ with them of hating America, being

against freedom, etc. Political opponents cease to be fellow citizens

and become enemies of the good. And such demonizing even takes place

within political parties. Some of the rhetoric in the race between

Bernie Sanders and Hillary Clinton embraces the idolatrous language of divine enemies, simply replacing enemy of God with enemy of good.

We Presbyterians

trace our theology back to John Calvin, and Calvinists have always

been particularly concerned about the sin of idolatry. When my

denomination's Book of Order outlines the central theological

themes of our tradition it includes this one. "The recognition of the

human tendency to idolatry and tyranny, which calls the people of God to

work for the transformation of society by seeking justice and living in

obedience to the Word of God." Idolatry and tyranny go hand in hand

because the moment we mistake our desires and purposes for God's (or for that of truth or goodness), we will find it

very easy to tyrannize those who disagree with us or oppose us.

For

Christians, the problem of sin, of idolatry, calls for confession, but

the language of confession, contrition, and repentance is rarely

encountered in our public or political discourse. Such language is

viewed as a sign of weakness. When questioned on whether he'd ever asked

God for forgiveness, Donald Trump replied, "I don't think so." Trump is

surely an extreme example, but he is far from unique. When politics

turns idolatrous, real confession becomes impossible.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

In the gospel lection for today, Jesus tells a parable that entraps the religious authorities. In this "Parable of the Wicked Tenants," an absentee landowner sends servants to collect his share of the vineyard's produce, only to have them beaten, abused, or killed. Finally, he sends his son saying, "They will respect my son." But they kill the son as well. Jesus then asks the religious authorities what the landowner will do. They answer that the landowner will "destroy" the tenants and give the vineyard to others, after which Jesus quotes verses from Psalm 118 that speak of a rejected stone becoming the cornerstone.

This parable is often understood as an allegory with Judaism as the tenants, Jesus as the son who is killed, and Christians as those now given the vineyard. Yet Jesus never says anything of the sort. It is the religious authorities who speak of the landowner destroying old tenants and finding new one. The parable clearly does indict the religious authorities (not Judaism), but they alone speak of destruction. And as the events of Holy Week and beyond unfold, the destruction those authorities imagined does not come to pass.

Instead, Jesus prays for forgiveness from the cross. Following Pentecost, Peter also extends the same forgiveness to those who "crucified and killed" Jesus. (Acts 2:14-42) God turns out to be little like the authorities' expectations of the landowner. Hardly surprising for this God whose ways are not our ways. Yet we keep presuming they are.

Click to learn more about the lectionary.

No comments:

Post a Comment