The report listed a number of performance areas such as worship and music, governance, morale, education, spiritual vitality, conflict management, and more. We were ranked above average in most of them but had two very low scores. We scored in the 21st percentile in an area we already knew was one to work on. When we saw this score we began discussing ways address it, suggesting ideas that might help us improve.

Then came our other low score, in the second percentile. That's correct, a 2. This would seem to be an area where we would work even harder to improve than the previous area, but the response was entirely different. Rather than suggestion on ways to improve, the discussion focused on why the score had to be wrong.

The first low score had produced no question about the score's validity, but the second score really unnerved us. It said something about us that we didn't want to hear, and so the survey instrument must be wrong. We eventually moved past this initial, knee-jerk reaction, although some still don't fully embrace the survey's findings. From my standpoint as a relatively new pastor (here just over four years), the findings are spot on, mirroring my experience of the congregation when I first arrived. But the findings are too out of sync with the congregation's self-image, too disturbing for some.

In the long run, I think the information from the survey will be a great benefit to us. We may not like the information, but we will make better decisions and plans if they are based in reality rather than in a more pleasing but false picture of ourselves.

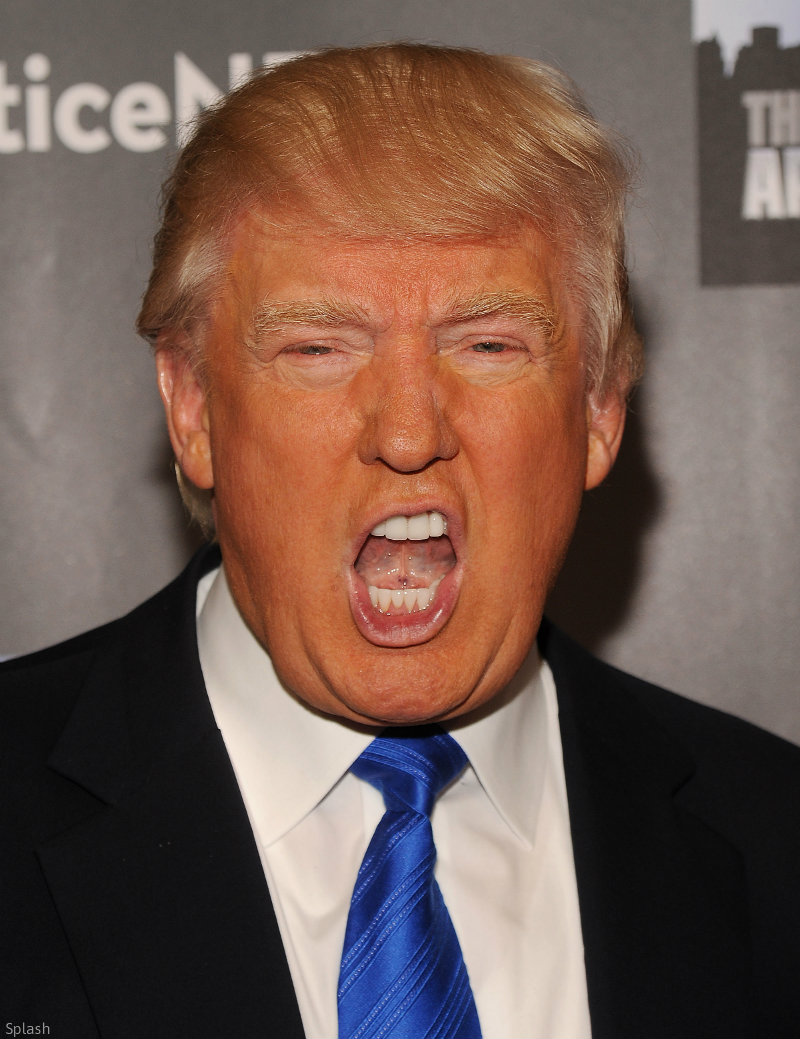

The success of Donald Trump's presidential campaign has provided our nation with a similar bit of helpful information, though it may be even more unnerving than that low score our congregation received. Trump's success has defied all manner of convention. It began with calling Mexicans "rapists" and move on to calls for banning Muslims from entering the country. At every step of the way, pundits and experts and lots of everyday folks assumed the campaign could not last. How could it with its regular appeals to fear and bigotry. Far too few Americans shared such views for Trump to garner the sort of support needed to win the nomination, much less a general election.

As Trump moved through the primaries and captured the nomination, people had to keep reassessing how this could be so. His success flew in the face of a self-image of America that many people held. You can hear it in the "This is not the America I know" statements that have been made following yet another statement by Trump that would seem to be so far outside accepted norms that it would surely doom his campaign.

Struggling to explain Trump's success while holding onto a vision of a tolerant, post-racial America is getting more and more difficult, not that people aren't trying. It reminds me a bit of our church leadership trying to hold onto its image of our congregation while making sense of that second percentile score. And just as it's helpful for our congregation to grapple with a self image that doesn't mirror reality, the same may be true of that America we thought we knew.

Trump's campaign success has placed a mirror in front of our faces, a mirror that reveals an image many of us don't like. I'm not suggesting that all of his supporters are racists or bigots, but clearly many are. Many others are perfectly willing to tolerate Trump's open flirting with white supremacists and others who seemed completely out of the mainstream not so long ago. And if we are willing to look in the mirror and not turn away, we may learn some hard truths that allow us to make better decisions and plans than we would by holding onto a more pleasing but false picture of ourselves.

***********************************

When the Supreme Court invalidated much of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, it did so in part because the America of 2013 was much changed from nearly 50 years earlier. The election of an African American president surely pointed to a very different racial landscape, and clearly things are different. They have changed and largely for the better, but the hope of many that racism and bigotry would simply fade away over time was overly optimistic.

I have my own, anecdotal evidence that says as much. I grew up in the South and still have occasion regularly to visit small town South Carolina. There I've witnessed college-educated, pillar-of-society sorts routinely use the N-word and explain their disgust for President Obama and his family as being because "They're just not like us." But perhaps my encounters are aberrations. Perhaps they don't represent a significant portion of the population, even in South Carolina or other parts of the deep south. But then along comes Donald Trump, appealing directly to this presumably fringe population and winning.

Perhaps Trump is an aberration, or the product of some perfect storm of middle and working class angst, economic uncertainty, dislike for Hillary Clinton, and more. Perhaps. But I think we would do well not to turn away from the glimpse of ourselves Trump's candidacy has provided. It is a gift, and like that unwelcome finding in the survey our congregation took, it may even guide us to a better future.

For those of us who find the view in the mirror of Donald Trump disturbing, perhaps it will jar us out of our complacency. Simply not being overtly racist ourselves is not enough. Many of us in mostly white, mainline congregations are especially culpable here. We quote Martin Luther King and preach tolerance; we're proud of ourselves for such tolerance, even as we worship in our mostly white churches and live in our largely white suburbs. Sometimes we even manage to enjoy our white privilege at the same time we're feeling smug about how open and tolerant we are.

But Trump has given us a mirror. Hopefully, we will make good use of the disturbing picture we've seen.