1 Timothy 2:1-7

God’s Desire, Salvation, and Us

James Sledge September 19, 2010

For me and many of my seminary classmates, one of the most intimidating things about becoming a pastor was taking something called ordination exams. These were separate from seminary itself, given by the denomination. And they were really scary because until you passed them all, you could not be ordained, and generally were not allowed to look for a job in a congregation.

And so, most Presbyterian seminaries offer help with these exams. Just prior to my last year of seminary, we had a seminar on how to take and pass these exams. They walked us through the process, talked about how the exams were structured, and shared wisdom gleaned from exams in previous years. One time honored piece of wisdom went, “If you are struggling with a theological question, you can never go wrong talking about the sovereignty of God.”

The absolute sovereignty of God, the idea that nothing operates outside of God’s ultimate control, is a centerpiece of John Calvin’s work, and Calvin is the founder of our theological tradition. And this focus on God’s sovereignty lies behind a doctrine often associated with Presbyterians: Predestination.

Now the fact is that predestination was not dreamed up by Calvin nor is it restricted to Presbyterians. Augustine came up with the idea that God’s salvation is a gift given to whomever God chooses some 1600 years ago. And so predestination found its way into Roman Catholic theology. When Martin Luther broke off from the Catholic Church about 500 years ago, he emphasized Augustine’s teachings on grace and salvation as a gift, and so he kept predestination as a Lutheran doctrine.

So how did we Presbyterians get stuck with the predestination label? Well, it seems Calvin got a bit carried away talking about God’s sovereignty. Calvin reasoned that if God was totally sovereign, if nothing could happen without God’s okay, then not only did God choose those who are saved, the members of the elect, but God must have also chosen not to save the others. This is a little something that became known as double predestination. Some are predestined for salvation and some for damnation.

Even Calvin found this a bit uncomfortable and said it was a difficult doctrine. And Presbyterians essentially called the doctrine off a century ago. But I’ve always wondered how Calvin could have come up with the doctrine in the first place considering today’s verses from 1 Timothy. Is says right there that God desires everyone to be saved. And if God is totally sovereign, if everything God wills will be, then that sounds more like universal salvation than double predestination.

God desires everyone to be saved. Jesus is the mediator between God and all humanity, and he died for everyone. You’d have a hard time coming to that conclusion listening to some Christians. In their version of the faith, God seems almost gleeful at the prospect of sending folks who won’t believe the right things into eternal punishment. But according to 1 Timothy, God would surely be distraught and weeping at the prospect.

God desires everyone to be saved. Jesus died for everyone. Of course that begs the question of just what it means to be saved, of just what Jesus’ death accomplished.

I have become more and more convinced over the years that the Church went badly astray when it began to speak of salvation, of being saved, in terms of an either/or, in or out category. In this view, saved has to do with us believing certain things and so getting our tickets punched for eternity. Jesus’ death is a part of the magic formula that makes all this work. And we’ve been talking this way for so many centuries that we hear Jesus and we hear the Bible with salvation already defined this way. But I’m pretty sure Jesus didn’t understand saved or salvation this way.

Not everyone seems to realize this, but Jesus was never a Christian. He was a Jew. And as a Jew, his preeminent picture of salvation, of God’s saving activity, was the Exodus story. Passover is the biggest Jewish festival and holiday because of this. It celebrates God saving Israel, which of course has nothing to do with going to heaven. It is about being freed from slavery, about safety and security, about being rescued from oppression.

And not only was Jesus a Jew, he also identified himself as a prophet. Israel’s prophets had taken the salvation story of Exodus and envisioned a salvation extended to all creation, perhaps best known in Isaiah’s peaceable kingdom. This prophetic view sees God’s saving acts in the Exodus as prefiguring a bigger act that will rescue all, that will bring all creation to freedom, safety, and security, that will rescue all from oppression. And these prophets speak of this as a new day, as a new age, something Jesus calls the Kingdom of God.

Of course, just as freeing the Israelite slaves was a threat to Egypt’s Pharaoh, the Kingdom of God is a threat to all worldly kingdoms and governments and systems. All such systems depend on certain inequalities. Some must be poor so others can be rich. Some must lose for others to win. Some must work hard so others can enjoy leisure. Some must be at the bottom so others can be at the top. Some must die so others can live.

But Jesus says that the Kingdom, God’s new day, the end of all such inequalities, has drawn near. No wonder they had to kill Jesus. Speaking of a new way to heaven wouldn’t have been a problem. But declaring an end to Rome’s empire, to all empires, and calling his followers to become citizens of that coming community rather than this current one, well that’s something that will get you in serious trouble.

But Jesus stays true to God’s vision. He will not adopt the ways of this age, and he will not fight the powers of this age on their terms. He will not engage in hatred and violence. His Kingdom is one of love and peace and acceptance, and it does not come by force. And so Jesus dies.

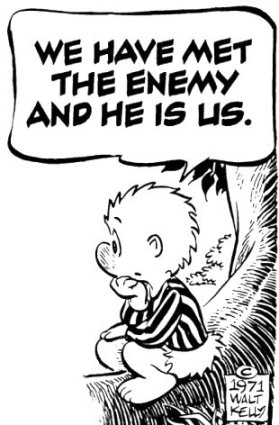

His death makes clear how far our ways are from God’s. It shows clearly how far the powers of this age will go to preserve their power. His death condemns us all, for all of us, to varying degrees, are willing participants in and self-proclaimed citizens of this age.

But Jesus’ death also makes clear that the lengths God goes to draw us toward that new age, that new day that has come near. Jesus is willing to bear the brunt of human foolishness, of our commitment to systems that are passing away. God loves everyone, desires for everyone to become a part of a renewed and redeemed creation, and so God will not lash out. Instead, in Jesus, God will weep, suffer, and die. God will gently beckon, and God will wait.

But God does not just wait. Jesus also calls those who will follow him to be witnesses to the hope of God’s new day, to show by their lives the living Jesus, God’s love in the flesh, God’s desire for all people everywhere. And so we heard a letter to the followers of Jesus urging that supplications, prayers, intercessions, and thanksgivings be made for everyone, including kings and those in high positions, the very people who sometimes persecuted and oppressed those early Christians.

God desires everyone to be saved. Jesus is the mediator between God and all humanity, and he died for everyone. And when we get caught up in this remarkable love and desire of God, when it takes root in our hearts, how can we help but see everyone with new eyes, with the eyes of Jesus. And when we do, how can we keep from sharing God’s love and embrace, with every single one of them?